Revocation of Accreditation for Danish Journalist Mathilde Kimer: Who and Why?

Revocation of Accreditation for Danish Journalist Mathilde Kimer: Who and Why?

Українською текст читайте тут.

On December 19, the Danish media began to write about the revocation of accreditation for work in the war zone in Ukraine of journalist Mathilde Kimer, a correspondent of the Danish public broadcaster DR. Kimer has been working in Ukraine for many years: she covered the Revolution of Dignity, the beginning of the war in 2014, interviewed Zelenskyy and Poroshenko, travelled to the occupied cities of Donetsk, Luhansk, and Crimea. DR didn’t have an office in Ukraine, but there was one in Russia, so Kimer occasionally worked and lived in Moscow. In 2022, she was nominated for the main Danish journalism award, the Cavling Prize, and in November, the Queen of Denmark awarded her the Ebbe Munck Award for her coverage of events in Ukraine and Russia.

The revocation of Kimer's accreditation in Ukraine caused a wave of critical publications in the media. Journalists linked this situation to Ukrainian-Danish relations: on that very day, December 19, President Zelenskyy asked the Danish government to provide Ukraine with new weapons, and the Danish parliament was discussing additional assistance to Ukraine. And although the Danish Foreign Minister said that his government ‘should not put itself in a position to exchange journalists for weapons systems,’ the Danish press did just that. For example, a program with the headline ‘Ukraine Strips Kimer of Accreditation and at the Same Time Asks Denmark for More Weapons’ was broadcast on Danish public television. Specialised media outlets, DR leadership, politicians, colleagues, as well as the Danish Union of Journalists, reacted to the revocation of Kimer’s accreditation, calling this decision ‘outrageous’ and asking the Danish Foreign Minister and the Ambassador of Ukraine to Denmark to renew the accreditation.

In turn, the European Federation of Journalists issued a statement claiming that ‘the Danish journalist was expelled’ from Ukraine. This is not true: revocation of accreditation does not result in expulsion from the country. Both the Security Service of Ukraine and Mathilde Kimer herself confirmed to Detector Media that the journalist was neither banned from entering Ukraine nor expelled from the country.

The European Federation of Journalists statement also said that Kimer is ‘one of a very few persons who has officially been banned from both Russia and Ukraine.’ Kimer was indeed banned from entering Russia on 1 August 2022, for ten years. To reiterate, she was not banned from Ukraine.

The website of Reporters Without Borders, an organisation that usually responds to violations of journalists’ rights, currently has no statement on the situation with Kimer. The journalist also received support from the Committee to Protect Journalists. Furthermore, the spokesman for freedom of speech at the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, Danish politician Mogens Jensen called for the restoration of the journalist’s accreditation. The new Danish Foreign Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen said that his ministry would do everything possible to get her back, adding that ‘Kimer’s journalistic integrity has never been put into question. Ukraine’s Ambassador to Denmark, Mykhailo Vydoinyk, in an interview with Politiken, said that the reason for the revocation of the journalist's accreditation was the violation of Ukrainian laws and rules of work in the occupied territories. He also called the statement that Kimer had been banned from working in Ukraine manipulative: the journalist cannot only work in places where battles take place. However, as Kimer herself told Detector Media, ‘In fact, accreditation is required everywhere. It can be checked anywhere, and it is virtually impossible to work without it.’ This is confirmed by journalists of other foreign media.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine did not answer our questions. ‘We are looking into the details of the decision made by the competent authorities and are cooperating with the Danish side to clarify all the circumstances,’ Foreign Ministry spokesman Oleh Nikolenko responded.

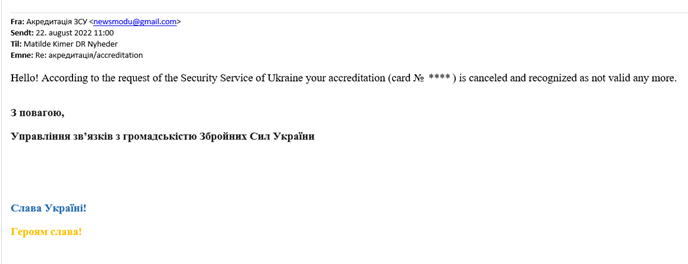

On December 19, the DR website published an article in which Matilde Kimer said that on August 22, she received a letter with a message informing her that by the decision of the Security Service of Ukraine, she was deprived of her journalistic accreditation. There was no explanation for the decision.

Kimer told Detector Media that the message was a surprise for her. She tried to contact the SBU spokesman Artem Dekhtiarenko for several weeks, but he did not answer. Detector Media asked Artem Dekhtiarenko for a comment on the words of Matilde Kimer, but the official replied that ‘the press service of the SBU does not provide any official comments’ on this matter.

Then, Kimer turned to the Danish Embassy for help. Embassy staff tried to contact the SBU to find out why the journalist was deprived of accreditation. The negotiations lasted almost a month. Massive missile attacks began on Ukraine just hours before the scheduled meeting. ‘Clearly, under such circumstances, it was not the right time to discuss my accreditation,’ the journalist said. The negotiations lasted for another two months, and in December, representatives of the embassy invited the journalist to Kyiv for a meeting with the SBU scheduled for December 8.

’I was in Denmark. It took me several days to get to Ukraine,’ Kimer said. According to her, representatives of the embassy had several meetings with the Security Service of Ukraine, and she attended only one. At the meeting, she was accused of travelling to Crimea and the occupied parts of the Luhansk and Donetsk regions in violation of Ukrainian law. ‘I replied that it was not true. I got there through a checkpoint, I think, in Kurakhove,’ the journalist said, showing Detector Media a photo of the stamp in her passport as proof, ‘I was in Crimea in 2015 and got there from Russia, but at that time it was not a violation of the law’. It is true the ban preventing foreigners from travelling to Crimea through Russia came into force in 2015.

From the conversation with the SBU officer, simply known as Oleh, Kimer began to understand that she was suspected of sympathising with Russia, spreading messages of Russian propaganda and Soviet symbols. ‘He told me that if people in the occupied territories of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions did not like me, I would not have been able to work there. And he said that I was promoting Soviet symbols, which is illegal. I was not directly told that I was a Russian agent, but it was clear that the SBU believed so,’ said Matilde Kimer.

These ‘rather vague’ claims, according to Kimer, are based on several of her Facebook posts about her work in the occupied territories five to six years ago. She also recalls the conflict situation in Mykolaiv in July 2022. ‘We were at the wrong checkpoint. We didn’t film anything, we didn’t do anything, we just weren’t supposed to be there. After that, I did a report about the military, and everything was fine. So I think that later someone looked at my Facebook page, which I hardly use, very occasionally I write something there because I have a lot of work and little time for it. Besides, I work for a half-million audience, not for six hundred [Facebook] friends,’ Kimer told Detector Media.

There is indeed not a lot of activity on Matilde Kimer's page. Recently, she has been posting links to the radio program Moskva-Kontoret (The Moscow Office), which she co-hosts with a colleague on DR. There are links to her reports from Russia and Ukraine, in particular from Crimea. There are photos from a report about a Russian fan of Soviet communism, from a parade in Donetsk, and photos from trips to the no-man’s land.

During the conversation with the SBU representative, Matilda Kimer came away with the impression that he had only read her Facebook page, rather than her journalistic work. At the end of the conversation, she asked if she could do something to get her accreditation back. ‘He said that for a few months — he did not specify how long — I can write “good stories” about Ukraine, and then, perhaps, the decision on accreditation will be reconsidered. I said that I don’t write articles at all – I work on radio and television, and for the last few months I couldn’t work at all. He said it wasn’t a problem, I could make some good stories, and they could provide me with photos and videos,’ the journalist said. She refused the offer, and the meeting came to an end. After that, according to Kimer, she left a flash drive with ten of her reports translated into Russian at the Danish Embassy so that the SBU would be able to get an idea of her work. Matilde Kimer does not know whether the SBU watched her video.

What happened in Mykolaiv? According to the journalist, she went to Mykolaiv with her driver and interpreter Ivan Kravtsov. Besides him, Kravtsov’s friend Pavlo and his girlfriend were in the car. The four of them drove from Kyiv to Odesa. On the way, Kimer found out that Kravtsov had not applied for an additional work permit in Mykolaiv and asked him to do it immediately.

In Mykolaiv, Pavlo met with a military man whose unit he planned to join. During the conversation with the soldier, Kravtsov asked Kimer if she wanted to make a story about the guys from that unit, which might have received new weapons. ‘A month before, I made a report from Donbas, where it was clear that Western weapons were very much needed, but had not yet arrived. I said I wanted to go, and we agreed to return when we had accreditation,’ the journalist said.

The next day, she and Kravtsov met with the press officer to discuss which military personnel she would work with in Mykolaiv. They met the correspondent of 1+1 TV Channel Nataliya Nahorna, who told Kimer the story of farmer Serhiy, whose field burned down due to shelling. She gave Serhiy’s contacts to Ivan Kravtsov while Kimer was on the phone with DR. Nataliya Nahorna confirmed this story to Detector Media, adding that she had warned the Danish journalist’s fixer that journalists should always be accompanied by a military press officer while in the field.

According to Kimer, the fixer did not tell her this, and they just went ahead. At that time, their accreditations were almost ready, but they had not yet been emailed. On the way, the car was stopped at a checkpoint; the military called the SBU. After several hours of waiting and clarification of the circumstances, the journalist was asked to leave Mykolaiv.

The next day, Kimer spoke to Nataliya Gumenyuk, a spokeswoman for the Operational Command South of the Ukrainian Ground Forces. Later, according to Kimer, Gumenyuk informed her that the issue was resolved. The journalist returned to Mykolaiv, made two reports and assumed that she had been cleared.

Nataliya Gumenyuk confirmed to Detector Media that she spoke with Kimer in July about this situation. ‘I was approached by press officer Dmytro Pletenchuk, who said that there was a problem with a journalist who was in the absence of military escort, that is, in violation of Order No. 73, at a facility where videotaping was prohibited. She claimed that she had an escort, saying that the person who accompanied her introduced himself as a military man who allegedly ‘could sort everything out. When Kimer talked to me, she already had a misunderstanding with the regional SBU office. The military warned her that she could not film in Mykolaiv, because her accreditation would be revoked after she broke the rules. I explained to her that there is an established procedure, that she had to contact us if she came to the area of our responsibility,’ said Nataliya Gumenyuk. According to her, the conversation was over the phone, and she did not see any documents, so she recommended the journalist sort it out with the ‘escort’ that had guaranteed her something. According to Gumenyuk, Kimer obeyed the military and the Security Service of Ukraine and left the city, but as a result of the violations, the military ‘was forced to raise the issue of depriving her of accreditation’. According to the military, the journalist was told that this would happen, although she was sure that the incident was over.

’We saw that she worked in the occupied parts of Ukraine,’ added Gumenyuk. ‘This alarmed us because she worked under enemy jurisdiction. We understand: journalists should cover the situation from different sides. But the enemy is the enemy. If he trusted this journalist, we may have doubts. But she was previously checked by the Security Service of Ukraine, and she received accreditation.’

Dmytro Pletenchuk did not answer the questions of Detector Media, saying that it was ‘beyond his competence’ to comment on the actions of the accreditation department or the Security Service of Ukraine.

The head of the Army Public Relations Department, Bohdan Senyk, told Detector Media that the military relies entirely on the recommendations of the Security Service of Ukraine when deciding on the accreditation revocation.

Officially, the Security Service of Ukraine does not comment on its decision and the meeting with Kimer. Unofficially, a source of Detector Media in the SBU, who wished to remain anonymous, confirmed both the fact of the meeting on December 8 and the content of the allegations that were put forward to the journalist. However, our source was not present at this meeting.

’The person who was there claims that Kimer admitted that she came to Mykolaiv in violation of the rules. She also asked how she could cover the events in Ukraine if her accreditation was taken away. She was offered information from official sources — our press service, and any other press service. But she has no right to be on the frontline,’ the source told Detector Media.

He says that Matilde Kimer’s accreditation was revoked at the request of the Security Service of Ukraine for violating the Order of the Commander-in-Chief №73. ‘Kimer, who had accreditation at the time, moved to the army positions in the Mykolaiv region and really wanted to film certain types of weapons, which I don’t even want to name because it is very important for us — and it was a priority target for the enemy,’ said Detector Media’s source in the SBU. ‘When the military saw this, they turned to us. The Security Service of Ukraine decided that the rules apply equally to everyone, and she should be stripped of her accreditation. Then the military asked us to check it in more detail.’

And here is what the SBU found. Matilda Kimer ‘graduated from a higher educational institution in Russia’ (according to Kimer, she studied one semester at Smolny University in Moscow in 2002).

’Lived in Moscow for a long time,’ (according to Kimer, she lived in Moscow in the following time periods: March — August 2009, December 2017 — September 2018, and July 2021 — February 2022; then her family returned to Denmark, and she moved to Ukraine; the Danish media report says that she has been living in Moscow since 2020).

’In violation of Ukrainian legislation, she repeatedly visited the occupied parts of the Luhansk and Donetsk regions, as well as Crimea through the territory of Russia.’ Two other sources of Detector Media within the special services say that Kimer travelled to the occupied territories of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions in compliance with Ukrainian law. Kimer has also repeatedly said that she went to Crimea through Russia in 2015, but her Facebook page also has photos from a trip to Crimea in 2016. A source in the SBU insists that the journalist was in the occupied territories illegally. It is impossible to check whether this is true. However, in 2015—2016, the SBU had nothing to say to Kimer.

There are discrepancies in the versions of the parties to the conflict, but we can try to recreate the general picture. The Danish journalist, who has been repeatedly checked by the Security Service of Ukraine over the past eight years, came to Mykolaiv and twice found herself in the wrong place — at a checkpoint and near the positions of the military, who had some secret weapons. According to her version, it happened due to a misunderstanding with her fixer.

The military saw these actions as a violation of Order №73, which regulates the work of the media in war. This is not the first conflict between the army public relations department and journalists who try to work outside the control of the military. This happened to several film crews working in the first days in liberated Kherson, for example. After the incident gained attention, at least some of the media got their accreditation back.

Local SBU officers started checking Kimer. More specifically, they looked at her Facebook page, which she doesn’t update often (unlike her Twitter), but posts photos from her trips there. We saw flags of Donetsk separatists, some nesting dolls in reports from Russia, photos from parades in Donetsk and holidays in Crimea. Two sources of Detector Media, one from the SBU and the other from the army, said that her work in Moscow and the fact that she called Donetsk pro-Russian militants ‘rebels’ and ‘told how they live a wonderful life’ aroused their suspicion. Although this was not the reason for the revocation of accreditation. Kimer believes that the SBU did not take into account her journalistic work at all.

Kimer also told her Danish colleagues that the SBU considered it suspicious that she had made phone calls to Russia several times during the full-scale invasion. Kimer still had an apartment there, and she said she asked someone she knew to water the flowers.

Another representative of the special service in a conversation with Detector Media described Matilde Kimer as a ‘decent person’ who had never been the target of any accusations. The same was said by two Ukrainian journalists who personally know Kimer: she cannot be suspected of sympathising with Russia, she is a professional person.

Analyst Dmytro Zolotukhin believes that the scandal was caused by the lack of clear communication from the SBU. Why did the service refuse to comment on its actions? ‘No law obliges us to report on the reasons for such a decision. We will not make excuses for the fact that we are persecuting some Kremlin mouthpieces,’ an SBU officer unofficially answered this question. In addition, he explained, it is better for the SBU not to express its position so that it does not have to change it publicly later. After all, through publicity and diplomatic efforts, Kimer may yet get her accreditation back.

Photo: Linda Johansen