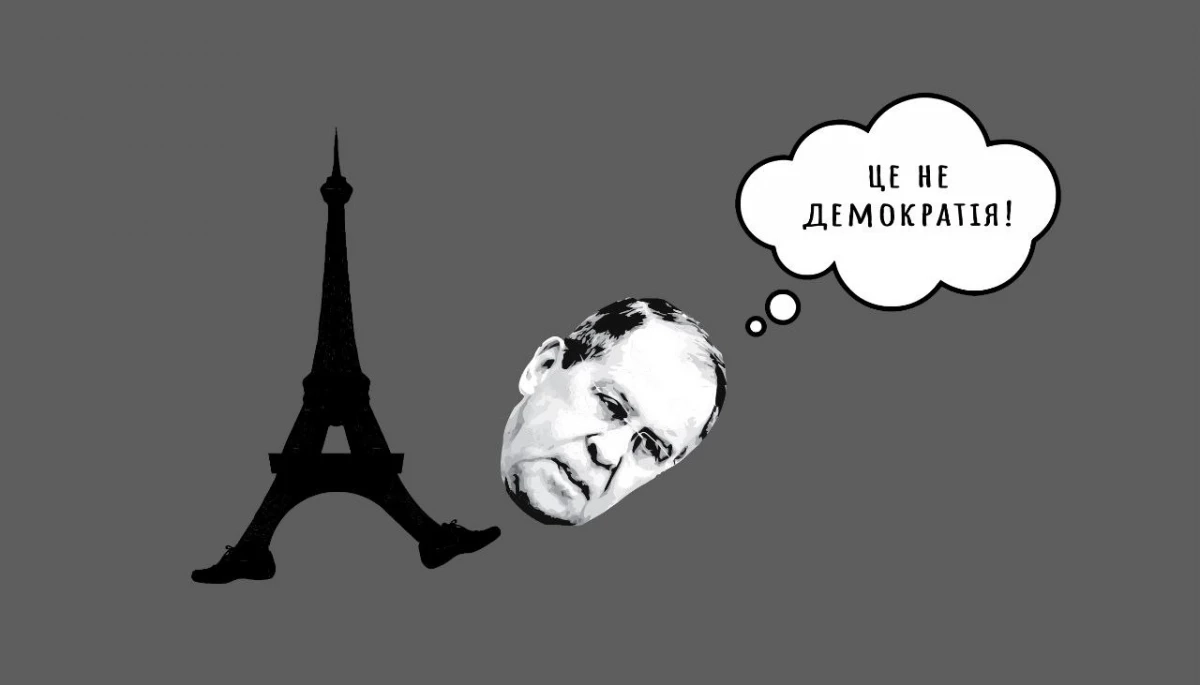

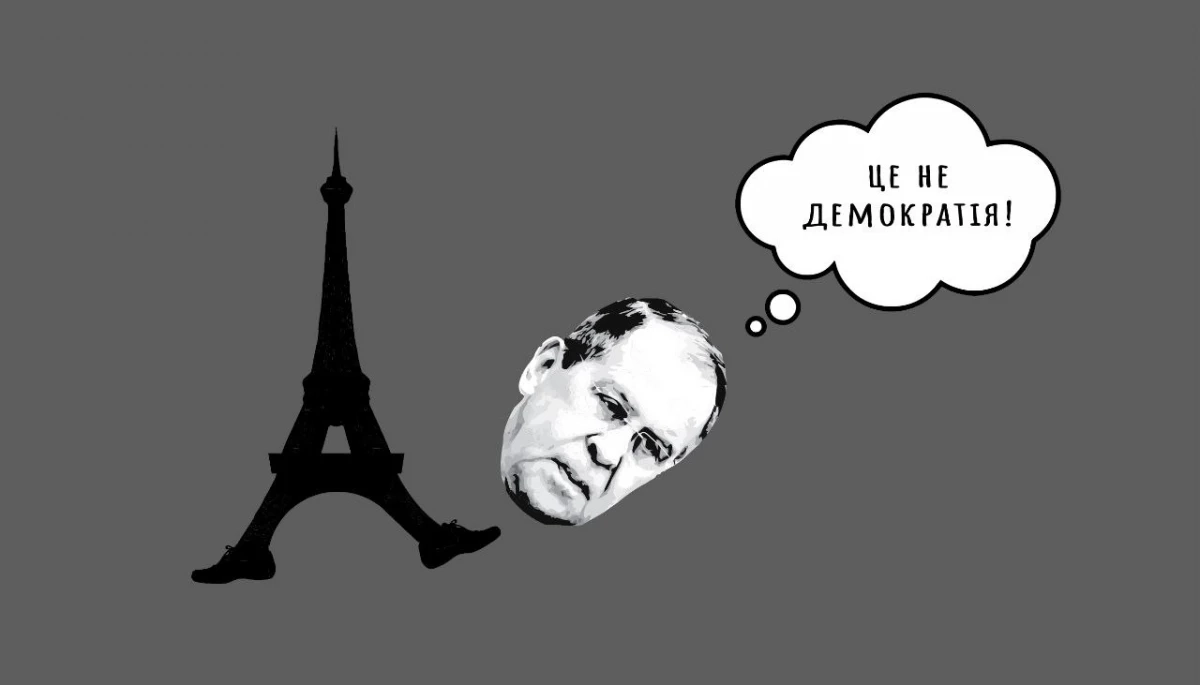

“Doesn’t Look Like Democracy”: Russian Propaganda on Elections in France and the UK

“Doesn’t Look Like Democracy”: Russian Propaganda on Elections in France and the UK

Українською читайте тут.

The first and second rounds of elections for the National Assembly, the lower house of the French Parliament, took place on June 30 and July 7. On July 4, elections were also held for the lower house of the UK Parliament, the House of Commons. The elections in France were held ahead of schedule following the dissolution of the National Assembly by the French president on June 9. Macron resorted to this dissolution in response to his party’s disappointing results in the European Parliament elections. Neither legal procedure nor political tradition compelled him to do so, thus this decision caused considerable surprise and speculation. Without this dissolution, the current assembly, where Macron had majority support, was set to work until June 2027.

Although the final date for the UK House of Commons elections was announced somewhat unexpectedly by the Conservative Party Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, it was anticipated and would have occurred no later than January 2025. The French elections maintained dramatic suspense until the end, now sending the Fifth Republic into a challenging period of coalition negotiations or a minority government. In the UK elections, the opposition Labour Party, led by Keir Starmer, won decisively, ending a 14-year period of Tory rule.

France and the United Kingdom, along with the USA, China, and Russia, are permanent members of the UN Security Council and representatives of the old nuclear club. Both countries are also allies of Ukraine. London was the first to provide Ukraine with main battle tanks and long-range weapons, specifically Storm Shadow cruise missiles, and it was the first to sign a security pact with Kyiv, committing to ten years of military support for Ukraine. Paris supplies Ukraine with similar long-range SCALP missiles. Furthermore, since February 2024, President Macron has rhetorically abandoned self-imposed restrictions on supporting Ukraine, even considering the deployment of French troops to Ukraine. This abandonment of the so-called “red lines,” which the West had drawn for itself at the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine to prevent escalation, is intended by Macron to create strategic uncertainty for Moscow, deterring its aggressive plans.

Throughout the war, Moscow has conducted massive informational attacks against Ukraine’s strongest partners, depending on the international context. We discuss the political consequences of the elections in France and the United Kingdom, how they have stirred the Russian propaganda machine, and the main talking points it has resorted to.

France Dives into Political Turbulence: Strong Flanks and Weak Center

Macron’s announcement of early elections was a true sensation for France, even for the president’s political allies. Despite the poor results of the pro-presidential coalition Besoin d’Europe (Need for Europe) in the European Parliament elections, neither legal procedures nor political tradition compelled Macron to take this step. In the June 9 European Parliament elections, the far-right Rassemblement National (National Rally) garnered 31.37% of the votes, while the pro-presidential coalition received 14.6%. Thus, the National Rally result was significant and alarming for the left and centrist forces. However, there was nothing unusual or new in the National Rally’s victory in the European elections, as this party had similarly won in France in the previous two European Parliament elections in 2014 and 2019, which did not correlate with its results in the national parliament and did not lead to domestic political crises.

The significant difference between national and European election results is explained by the different legal procedures, the specific political culture of France, and the different political and informational contexts of each election campaign. The European Parliament does not directly influence France’s domestic policy, and voter turnout in European elections is traditionally low. However, these elections become a good opportunity for protest votes against Brussels bureaucracy. The anti-immigrant and Eurosceptic rhetoric of the National Rally resonates well with a significant portion of voters in such an election campaign. Additionally, European elections are held under a proportional system, allowing the consolidated radical right to show high results amidst the fragmentation of other political forces. In contrast, elections to the National Assembly are held under a two-round majority system, which traditionally reduces the representation of radical forces in parliament.

There are different interpretations of Macron’s decision to dissolve the parliament amid his low ratings. The newspaper Le Monde suggests that Macron’s advisers feared the gradual disintegration of the pro-presidential coalition in the parliament against the backdrop of Macron’s weakened electoral standing. Thus, the decision to hold new elections could give Macron a ratings boost and a chance to renew the parliament with a more loyal body of MPs. Macron likely intended to lead the “republican front,” an informal alliance of centrist and leftist forces in France aimed at preventing the far-right from gaining power. This tradition of unity dates back to the 1956 parliamentary campaign, where an atypical coalition sought to prevent the Pujadists, the ideological predecessors of the National Rally, from coming to power. Given the fragmentation of the French left political spectrum, the limited time to reformat the political landscape before unexpected elections, and Macron’s party’s second-place finish in the European elections, his strength could be perceived by voters as the main opposition to the far-right’s rise to power.

However, the left managed to form a broad alliance quickly, the Nouveau Front Populaire (New Popular Front), which included more than 20 parties, from moderate Greens and Socialists to far-left Communists and Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise (Unbowed France). This broad left coalition became the center of gravity for the “republican front,” mobilizing both large-scale protests against the far-right and voter turnout during the short campaign period.

In the first round of elections, with a record turnout of almost 67%, the far-right National Rally won with over 33% and secured 39 seats in the National Assembly (totaling 577 MPs) in the first round. The second place went to the left coalition of the New Popular Front with over 28% and 31 guaranteed seats. The presidential coalition Ensemble (Together) received less than 22% and won in the first round in only two constituencies. The once-powerful center-right party, Les Républicains (The Republicans), garnered just 7%. Before the elections, it split because party leader Éric Ciotti was willing to form a coalition with the far-right, which most of his party members did not support.

To win in the first round, a candidate in his or her constituency must receive more than 50% of the votes cast, representing at least 25% of the registered voters in the constituency. If no candidate in a constituency achieves this, the two highest-scoring candidates plus any other candidate who garners at least 12.5% of the total number of registered voters advance to the second round. The candidate with the highest number of votes is elected in the second round. So although the far-right demonstrated leadership, suspense remained until the second round in most districts.

The fate of the parliament was decided in so-called triangles: candidates from the far-right National Rally, the left New Popular Front, and centrists from Macron’s coalition Together. The solidarity of the “republican front” tradition came into play. Centrists or leftists withdrew from the race in over 200 constituencies in favor of their more popular former opponents to prevent far-right victories. This solidarity campaign received significant public support, with even the leader of the French national football team, Kylian Mbappé, using his platform to oppose the far-right while participating in the European Championship in Germany. However, the left were the ones who benefited the most from this solidarity.

In the second round, the New Popular Front took first place with 182 parliamentary seats. Macron’s presidential coalition Together is in second place with 168 seats, and the right-wing populist party National Rally is in third place with 143 seats. For a majority, it is necessary to win 289 seats. Therefore, France will face difficult coalition negotiations or a minority government. The longtime leader of the National Rally, Marine Le Pen, demonstrated confidence despite her third place, emphasizing that she would double the number of MPs from her political force, “I have too much experience to be disappointed with the result when we double the number of our deputies... The wave continues to grow... Our victory is only postponed.” French Prime Minister Gabriel Attal resigned after the election, but Macron did not accept it. In any case, Paris is facing an era of political turbulence, with the left and right spectrum of the political field now dominating the center.

Russian Propaganda Reaction: “France Brought to Its Knees”

Russian propaganda during the campaign expressed the greatest sympathy for the far-right National Rally and its leader Marine Le Pen. In the 2022 presidential elections, Marine Le Pen was Macron’s main competitor, finishing the second round with 41.46% of the vote. Since then, she has remained a critic of the centrist government. Regarding support for Ukraine in its war against Russia, Le Pen holds a characteristically soft stance toward Russia, common among European far-right politicians. Ahead of the second round of parliamentary elections, Le Pen stated in an interview with CNN that her party would not allow French weapons to be used for strikes on Russian territory and would prevent “French boots from stepping on Ukrainian soil.”

Since the beginning of her political career, Marine Le Pen has had a sentimental attitude towards Russia and Putin, whom she called “the defender of the Christian heritage of European civilization” in 2014. Le Pen’s closeness to Russia is also marked by a €9 million loan her party received from a Russian bank in 2014.

However, amid Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, Le Pen’s rhetoric regarding Putin has cooled significantly, “If Russia wins the war, it will be a disaster because all countries that have a territorial conflict will think that they can resolve it with weapons.” Nevertheless, her position differs from Macron’s in that Ukraine’s victory in this war is also seen as an undesirable outcome by Le Pen, who believes that “Ukraine, without NATO’s strength, cannot defeat Russia militarily, and NATO’s involvement would mean the start of World War III.” Le Pen has repeatedly raised the issue of supplying weapons to Ukraine, arguing that continuing to send arms to Ukraine “threatens a new Hundred Years’ War.” Her primary approach to the Russia-Ukraine war is an immediate ceasefire and the start of negotiations. In this, Le Pen is not much different from the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

In contrast, the rhetoric of the nominal leader of the National Rally, Jordan Bardella, who ran as the party’s candidate for the future prime minister, is more favorable towards Ukraine. Bardella stated that if his party came to power, he would not allow Russia to “absorb Ukraine” and declared his readiness to oppose Russia if he became prime minister.

Ahead of the second round, Russian propaganda media were optimistic about Le Pen’s victory and securing an absolute parliamentary majority in France. In their articles, propagandists described the adverse consequences of Le Pen’s victory for Ukraine and the West in their confrontation with Moscow. They particularly highlighted Le Pen’s words about prohibiting the use of French long-range weapons for strikes deep into Russia.

In an article titled Le Pen Pledges to Block Troop Deployment to Ukraine, RussiaToday made sharp assessments about the potential victory of the National Rally in France. According to RT contributors, Le Pen’s party “could take radical measures, including ending any support for Ukraine or even completely withdrawing France from the US-led NATO bloc.” The topic of France’s withdrawal from NATO was frequently covered by Russian media. Drawing on France’s experience of leaving NATO’s military command structure in 1966 under President Charles de Gaulle, Russian political analysts predicted a repeat of history. They suggested that France might follow the 1966 scenario and implement a “soft exit” from NATO, leaving military command while limiting participation in joint missions to a small number of troops.

Propaganda was not silent on the topic of “election fraud” in France. RT published an article titled ‘Putin endorsed Le Pen’: Russiagate comes to France, in which they mocked French newspaper Le Monde’s information about Russian interference in the parliamentary elections. The term Russiagate derives from the Watergate scandal in the US, which led to the US Congress initiating impeachment proceedings against the president. Following this incident, the practice of naming major scandals with the suffix -gate became popular worldwide. In the case of Russiagate, this suffix is used humorously, and the term refers to any financial or organizational ties with Russia or Russian interference in election processes.

The impetus for publishing this article was a post by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the social network X, suggesting that the French public desires a “sovereign foreign policy” and an end to the “dictates of the US and EU” if Le Pen wins. The RT article supports the Ministry’s position, labeling European politicians as corrupt. The propaganda piece contrasts the “very mild message” from the Ministry with the “open calls from the West for regime change in Russia, endorsement of violence, murder, and terrorism,” accusing Western countries of interfering in Russia’s internal affairs. In response to such provocations, Le Pen expressed her outrage, calling the Russian Ministry’s tweet a “form of interference,” and stated she feels “absolutely no responsibility for Russian provocations.”

Sputnik also claimed that it doesn’t matter what government is formed in France or who becomes prime minister because due to Macron’s policy of “fully engaging in the war in Ukraine to support the Zelenskyy regime,” the country has fallen into “phenomenal debt.” Propagandists in the same article reference France’s external debt of €3 trillion, calling it an “unpayable amount.” Russian media write that “France is being brought to its knees,” and regardless of the election results, the country “no longer has the means for its own policy.” They also pushed the idea that without an absolute majority in parliament, indicating Le Pen’s defeat in the elections, “the country will be unable to be governed properly, and we will observe a crisis.”

Propagandists justify Le Pen’s popularity and her party’s rise by pointing to the alleged weakness and ineffectiveness of Macron’s government. Moreover, RT published a piece describing national and EU elections as “not just a slap in the face for the ruling party… but revenge for the controversial 2005 referendum.” They suggest that French citizens are outraged by the government’s decision to adopt the “European Constitution… with minor changes” despite the negative referendum outcome, referring to the Lisbon Treaty, which differs significantly from its original draft. According to this narrative, French citizens decided to punish Macron after 20 years when the government openly ignored the people’s will. However, these arguments lack logic, given that it was Nicolas Sarközy, a center-right Gaullist, who decided to ratify the Lisbon Treaty, not the centrist Macron.

Following the announcement of the National Assembly election results, Russian propaganda began spreading assertions about growing instability in France and the fragility of the future government. RT and Sputnik published reports about protests in Paris by dissatisfied voters “from both ends of the political spectrum, highly displeased with Macron’s presidency.” According to propagandists, these violent protests are supposedly “the work of small groups of political agitators, often with the current government’s connivance, aiming to create an atmosphere of unrest and chaos.”

Propagandists call the lack of an absolute majority for any political force and the need to form a coalition government with parties of different ideological orientations a crisis, and they predict that Macron will resign soon. Another alleged scenario suggested by the Russian media suggests the formation of a “technical government” to maintain stability, with Macron potentially dissolving parliament again a year after the elections.

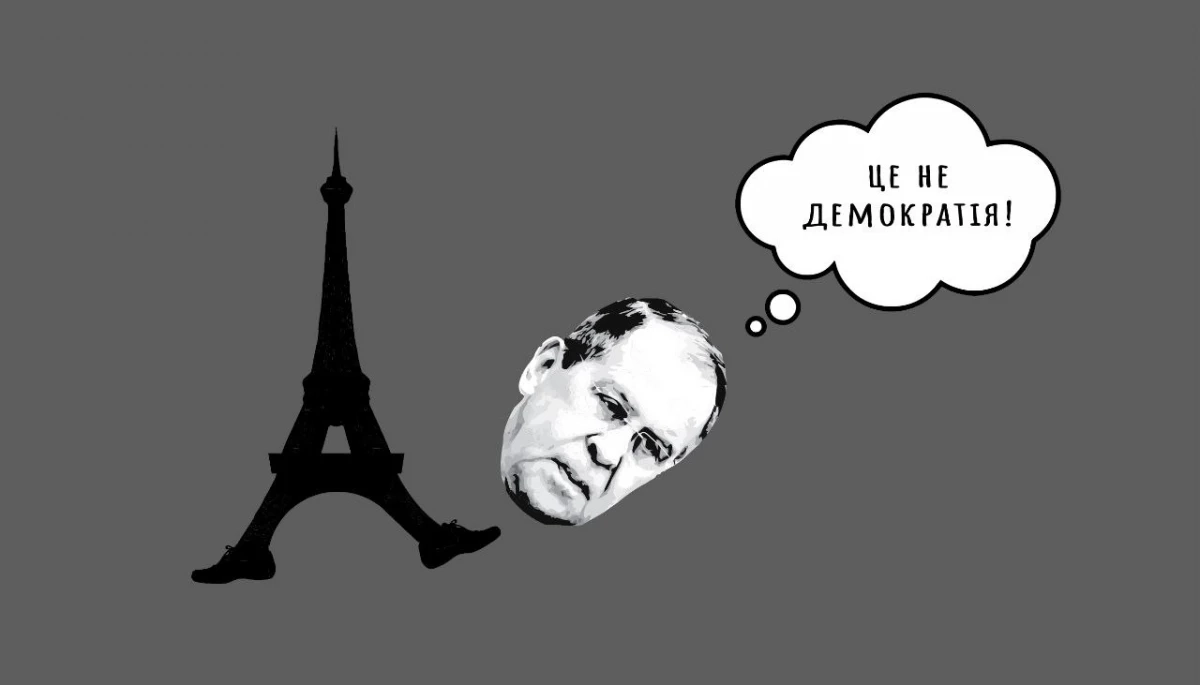

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov even criticized the practice of withdrawing candidacies during the second round of elections. He stated that such elections “don’t look like democracy,” arguing that the second round “was designed precisely to manipulate voter intentions during the first round when some candidates can withdraw.” It is worth noting that these criticisms of the democratic nature of the elections come from a country ranked 144th out of 167 in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index.

Russian Propaganda Talking Points About Parliamentary Elections in France and the UK

“Support for Ukraine undermines voter trust”

“European leaders are incapable of solving domestic issues”

“Election procedures are undemocratic”

Change in London, but Not in Ukraine Support Policy

In contrast to France, the elections in the United Kingdom were much more predictable. During the current parliamentary term, the ruling Conservative Party saw three different leaders and prime ministers: Boris Johnson, Liz Truss, and Rishi Sunak. Each leadership change was accompanied by scandals. Consequently, on July 4, the opposition center-left Labour Party achieved a predictable victory, winning 412 constituencies and thus forming a solid majority in the 650-seat House of Commons (with 326 seats needed for a majority). The Labour faction grew by 211 MPs, while the Conservatives won only 121 seats, losing 251.

Notably, Labour’s performance in relative percentage terms was less impressive. The party secured 33.8% of the vote, just under 2% more than in 2019. Labour’s convincing result was primarily due to the weakness of its main rival, the Conservative Party, which, under the majority electoral system, failed to maintain its positions in most constituencies and ceded ground to its former challengers.

A significant portion of the Conservative voters were drawn away by Nigel Farage’s far-right Eurosceptic Reform UK party, which, despite securing 14.3% of the vote, won only 5 seats. Representatives of the Labour Party and its leader, and now Prime Minister, Keir Starmer, have repeatedly stated that under the new government, the consistent support for Ukraine will not weaken. However, a long-term risk for Ukraine is the strengthening of far-right forces in British politics, particularly Farage’s party, whose voters mainstream parties will inevitably consider in their future political strategies.

Russian Propaganda Bets on the Far Right Once Again

On the eve of the House of Commons elections, Farage delivered a speech questioning the UK’s support for Ukraine, which was heavily quoted by Russian propaganda media.

In an interview before the elections, Farage effectively blamed NATO for the war in Ukraine, “It was obvious to me that the ever-eastward expansion of NATO and the European Union was giving this man [Putin — DM] a reason... to go to war.” Such statements provoked an outraged response from Rishi Sunak, who said that Farage’s claim was “completely wrong and only plays into Putin’s hands.” Russian propaganda media featured articles on Farage, portraying him as an independent politician being discredited through accusations of ties with Russia.

The Russian ambassador to the UK stated he anticipated accusations of election interference from Russia — and such accusations indeed emerged. According to an investigation by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, five Facebook accounts “spread pro-Kremlin propaganda” in support of Nigel Farage’s populist Reform UK party. Farage, in turn, dismissed any allegations of ties with Russia, calling claims of his sympathies towards Putin the “Russia hoax”.

Some of Farage’s statements were echoed by propagandist media due to their compatibility with Russian propaganda narratives. For instance, Farage addressed the topic of mobilization, stating that “Ukraine has no hope against Russia on the battlefield due to lack of manpower” and that, as a result, “there may be no young men left in Ukraine.” RT built its traditional talking points around this quote, blaming the President of Ukraine for the war, as if “Zelensky decides whether to cede territory to stop the bloodshed.” There was also rhetoric about the need for reconciliation, with Farage asserting that “no one is even talking about peace,” only that Ukraine will win, which Farage finds unrealistic. Instead, he said, “some attempt to broker negotiations between these two sides needs to happen,” resonating with the positions of other pro-Russian far-right politicians in Europe, such as Viktor Orban, the “dove of peace,” who continues his tour to promote his concept of reconciliation.

While covering the UK elections, Russian propaganda aimed to discredit the newly elected Prime Minister Keir Starmer and devalue the Labour Party’s victory. The day after Starmer’s term began, the propagandist outlet Sputnik published an article titled UK PM Starmer Committed to Maintaining Western Hegemony With British Nukes, painting the new prime minister as a nuclear aggressor. The basis for this attempt at discreditation was Starmer’s campaign statements about the readiness to use nuclear weapons. Starmer aimed to enhance national security by increasing defense spending, building new nuclear submarines, and ensuring Britain’s continuous nuclear deterrence at sea. Sputnik’s article mentioned the UK’s nuclear doctrine, which states that the country has the right to launch a preemptive nuclear strike. Based on this, Russian propaganda began accusing the UK of potentially using nuclear weapons against non-nuclear states. In an attempt to discredit the Labour government’s intentions, the outlet appealed to emotions, suggesting that due to the UK’s “commitment to increasing its nuclear arsenal,” there was a threat of “even greater casualties.”

Russian propaganda media fueled the topic of the UK’s aggressive foreign policy with comments from former RT host and ex-Member of Parliament George Galloway. The latter alleged that the UK would find itself at war within six months of Starmer’s election as prime minister. According to RT, the same fate awaits the USA if Biden is elected president. Supposedly, the cause of large external wars will be the will of the “global elites who control most Western democracies and are committed to the idea of a ‘quasi-cold war,’ which will facilitate the expansion of the shaky American empire.” Signs that Starmer “sold national interests” to global elites, according to Russian propagandists, include “mass immigration, zero carbon emissions, transgender rights, and the proxy war in Ukraine.”

The overall political landscape in the elections is presented as lacking alternatives. Russian propagandists describe candidates in the UK elections as “fourth-rate politicians,” portraying their overall inefficiency, and the actions of Rishi Sunak’s government are said to “provoke laughter.” Therefore, Russian propaganda portrays the Labour Party’s victory not as their merit but as a consequence of Conservative failures, with the war in Ukraine playing a prominent role in those failures.

Propagandists at Sputnik speculate that the UK’s desire to “pour money into the West’s war against Russia in Ukraine” raised the inflation rate “to a 40-year high in 2022.” The UK’s economy contracted throughout 2023, which they claim signals the beginning of a recession. Additionally, propagandists attribute negative effects to the sanctions imposed on Russia. These sanctions supposedly “drastically impacted European economies, causing inflation and rising energy prices.” The restrictions on importing Russian gas to the UK “particularly hurt household finances.” Thus, the agitprop reiterates that the UK’s pro-Ukrainian stance is the root cause of all the misfortunes faced by UK residents and that the Labour Party’s rise to power resulted from the desperation of British citizens disillusioned with Conservative policies.

According to Sputnik, one reason for the loss of popularity among European politicians was their “support for Western imperialism in Ukraine and Palestine,” which ultimately discredits establishment political forces “on both sides of the Atlantic.” The general trend in propagandist media was to convince their audience of the failure of the policies of European leaders who support Ukraine in its war against Russia. Consequently, Russian media articles suggested that the elections in the UK and France “revealed the absolute bankruptcy of politics in modern Western liberal democracies,” which allegedly demonstrated the inability of political leaders to solve problems in their countries. Russian propaganda tried to justify the “inevitability of internal political division and decline” in Western states, portraying the elections as the beginning of a prolonged crisis.

A common trend in covering the elections in France and the UK was also a “preemptive reaction” regarding election interference. Russian propagandists preemptively mocked the idea that the West might report instances of Russian interference in the elections, and later, any real evidence of Russian involvement in the electoral processes of the two countries was presented as doctored material aimed at discrediting Russia.

The main common message promoted by the Russian propaganda machine was the idea of European citizens’ dissatisfaction with their current governments. Politicians like Rishi Sunak, Emmanuel Macron, and Olaf Scholz were characterized as “fiercely bent on escalating the conflict in Ukraine,” particularly in an RT article, and as incompetent, weak leaders who failed to fulfill their campaign promises. In contrast, Russian propaganda portrays far-right populists as positive figures who restrain escalation efforts and do not want to “come to terms with the catastrophic consequences of flawed foreign policies,” primarily referring to the support of Ukraine. Thus, Russian publications create the perception among their readers that centrist politicians, allegedly “controlled by EU and US bureaucracies through NATO,” are weak figures, whereas right-wing populists, according to the propagandists, “demonstrate strength and independence of views, enjoying greater popularity,” as mentioned by Sputnik, among others.