How schoolchildren in Sweden are prepared for life in the "post-truth" age

How schoolchildren in Sweden are prepared for life in the "post-truth" age

"We cannot engage in propaganda to any extend. Our task is to show objects from different sides. We can express our opinion, but we must not put pressure on students", says Lars Erik Hal, elementary school teacher in one of the Swedish schools.

Sweden is a country which regularly ranks among the first in the development indices and ratings of the most prosperous states. Of course, it is interesting how the education system in such a successful country is organized and what values are in its basis.

I was able to delve into this topic during the Media Literacy School, which was organized by the Fojo media institute in March. Together with 24 more participants, we got acquainted with school teachers, visited gymnasiums and talked to students. The main goal was to see how critical thinking and digital technologies were integrated into education. Being interested in media topics, we became convinced that the main role in schools plays the attention to the psychological state of students, trust between teachers and schoolchildren, respect for the individuality and opinion of the child.

How is the school education organized?

Everything begins with preschool education (Swedish – Förskola) at the age of 1-5 years. Then, when the child is 6, they come the so-called zero grade (Förskoleklass): if earlier parents could choose whether a child should study in it, now, since 2018, the zero grade has become mandatory. From 7 to 16 students go to regular school (Grundskola), from 16 to 19 years they study in gymnasium (Gymnasieskola). In gymnasium, you can study in one of 18 directions: twelve of them are vocational, and six are theoretical, which prepare for entering the university. It is very difficult to enroll to some very popular of them.

Gymnasium of Oskarshamn. Part of the premises is workshops, where students of technical specialties are taught vehicle mechanics, metalwork, welding and so on.

In Sweden, there are private schools and municipal schools. In municipal schools, basic education is free of charge but for additional options you need to pay extra (for example, an extended day group); however, the supplement is differentiated depending on the income of the parents.

Schools are guided by the law on education, there are also school rules which are written by the student council and parents; these rules are approved by the director. For each class there are also separate specific rules which are made by the students.

Until the sixth grade, marks as such are not used in schools: the teacher puts color symbols on the works (green on excellent, light green on good, yellow on those which need to be improved). In the upper grades the evaluation system with A, B, C, D, E and F marks works.

Trust relationship

Lars-Eric Hal is now a pensioner, and concurrently he is a teacher of junior classes. According to his own words, he is a 20% of a teacher, and 80% of a pensioner. He teaches at the school of the city of Nessjö where 30 thousand inhabitants live. Lars told about his experience working in different schools in Sweden: mostly he occupied the positions of an IT teacher, of a class teacher, of a "special teacher" (for teaching children with special needs).

Lars-Eric Hal, former consultant of the educational website "Media Compass", currently a primary school teacher.

He told that sometimes he had to teach subjects that were far from his own specialization: for example, music or art. "If it came to music, I basically turned on audio records for the students and asked them to guess what kind of composition it was", Lars laughs. He explained that for Grundskola it is not unusual for a class teacher to replace other teachers: "Good relations with students and a friendly environment are very important. Since the main thing is not what we tell in the lesson, but what the students perceive and how well they do it. And the perception will be most comfortable and effective if what is said comes from a person you know and trust."

The physical and psychological comfort of schoolchildren is provided in different ways. There is a "health team" (it is one for several schools), which includes a school doctor, a nurse, a curator, a speech therapist and a psychologist. Once a week, this group has a general meeting with the school director. Each school has a special teacher who pays attention to children with special needs.

In addition, there is a "team to ensure a fair attitude to each student." It includes both teachers and students – one from each class (except the youngest). The task of this team is to notice in time if one of the children has any problems, such as frequent bad mood, unwillingness to communicate and strained relations with classmates. Students from the "support group" undergo special training with a psychologist. "The other children have a very respectful attitude to them and many express a desire to take such a role on them", Lars replies to the question of whether there is a prejudice among children towards "students-psychologists".

Digital technologies at school

"In our school, each student has his own tablet, which already contains some training applications. Gradually, within three years, the whole Swedish school system should change to such a system," Lars explained.

The use of digital technologies in education is an actual and already habitual topic today. In the Swedish school, it was interesting to learn not only about the provision of material needs, but also about the conceptual filling of the digitalization. Tablets and smartboards in each class are expected, but more importantly, the digital here is not just another tool: the new digital approach is part of the curriculum.

From July 1, 2018, an update to the law on education will come into force; it determines what specifically needs to be taught in the 'digital' field in each school subject. Specifically, programming will be a compulsory element of such subjects as mathematics and technology. "Here the problem is obvious that the teachers know less than the students in the field of programming. But it is important not to be shy about getting help and asking the children", Lars says. In addition, the Swedish School Administration has created a training portal in digitalization for teachers; there it is possible to find materials concerning how digital skills and work with media can be integrated into different subjects and why it should be done at all.

Lars said that a lot of digital tools are being used at the school. In addition to those already mentioned, these are audio versions of texts of all textbooks, Office 365, Power Point, pedagogical videos, feedback from students using the Traffic light application (the idea behind the application is that students at the end or during the lesson can send a "signal" to the teacher, telling how far they understand the topic).

More complex use of technology:

- implementation of the concept of "write in order to read" (students work with a computer, listen to text in headphones and type it);

- "flipped classroom" (the teacher gives material for independent study at home, and in the lesson, there is a practical reinforcing of the material, while actively using audio and video formats);

- method of joint writing (a group of students works together – each writes, for example, an introductory part to a story, then these fragments are alternately displayed on a common screen, it is discussed together, then they again return to their work, sometimes making corrections to the texts).

Lars explains that technical supply is really expensive and local authorities are not always ready to finance it: "The main argument on our part is that we achieve educational goals more effectively with the help of digitalization. We invite students to meetings with politicians who make decisions so that they can tell why digital technologies are important for them."

"But we must remember that the digital tools do not diminish the role of the teacher," he adds. "It should be equally active and included in the process, regardless of the number of technologies."

Media literacy in the classroom

"In Sweden, the teacher's task is to teach the student to work with the media and to critically analyze the information. We often talk about the school's compensatory mission, because all children, regardless of the social environment or of their surroundings, should receive an equally qualitative and effective education in the field of media," says Angelin Skepner, a teacher of Swedish and English at the gymnasium.

These words represent the central idea around which the media education system is built. Different schools may have their own specifics, but a critical analysis of media – websites, social networks, television – is built into different subjects. A separate activity is media production.

Angelin said that English and Swedish are some of the most convenient subjects for including work with media. So, the lesson often begins with a discussion of world news. "In the English lessons we talk about politics from time to time. For example, our students know a lot about Donald Trump, as well as his attitude to the media, about fakes and "post-truth," Angelin says.

Angelin Skepner, a teacher of Swedish and English in the gymnasium of Oskarshamn: "If we want to be active citizens involved in the educational process, we must think critically."

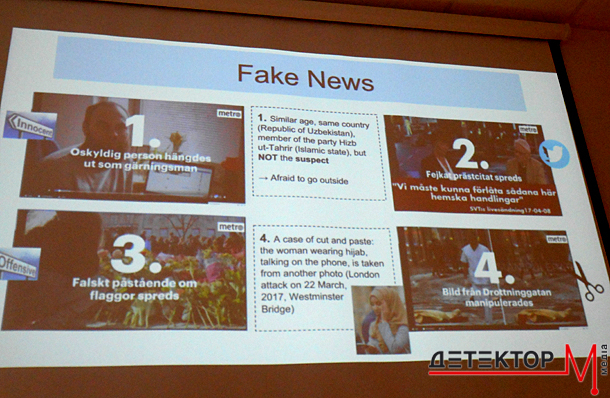

After the terrorist attack in Stockholm on April 7, 2017, Angelina invited the students to see how the Swedish and world media covered this topic. The students discussed the headlines, as well as illustrations to the materials, which photos were used – that is how they came to the conclusion that the world media showed more close-up shots and details from the scene than the Swedish media. In addition, ethical issues – what is appropriate and what is not – were discussed with the students. Using the materials of the Swedish fact-checking project Viralgranskaren (we published an interview with its editor), the students saw that the journalists made a mistake in coverage – they called the suspect a murderer ahead of time (he was not a murderer, as it turned out later).

"During the discussion, I needed to be cautious, because the students in the class personally knew people who witnessed the terrorist attack," Angelin said.

Lars-Eric Hal says that over the years he worked as a teacher, he often turned to the media to explain complex issues related to law and social studies. For example, he asked students to find notes and materials on the topic of women's rights and the criminal situation in the city; then all of them were examined and we analyzed them together. Now, students work less often with newspapers and magazines.

"When there were Olympic Games in Sochi, at the lesson of geography, I suggested to schoolchildren to explore the location of the games using online tools. They found this city in Google Maps; then they looked at it with the help of webcams. I also brought them a magazine with an article about the games – the title was A Game Which Has Two Faces – and invited the students to think why an article could be called that way," Lars says.

Media Day and the role of libraries

In each school, the so-called Media Day, which is devoted to the discussion of media literacy issues, is held once a year. On such a day, a special guest appears in schools – Joran Andersson, curator of our school FOJO; now Joran is retired, and in the past he worked as a school director for 20 years and for 12 years he was a media pedagogue of the project called "Media Compass".

Joran Andersson in the Fojo media institute

"On the media day, we collect students, mostly from 8th-9th grade, around three hundred people, – Joran says. As a rule, I as well as the representative of the local newspaper editorial office and Ula Sigvardsson, our press ombudsman, speak in front of them. We talk about different aspects of media. In general, I am meeting with a few thousand students on the media days. And some time before, I contact the teachers and we are preparing assignments so that the students fulfill them until that day."

In gymnasiums there are subjects devoted only to media production; there, students try on the role of journalists themselves – they learn to write texts, to make videos, to prepare video programs and to process photographs. There are also subjects in the gymnasium that are devoted to the study of media in general. For example, the subject "Society and Communications" examines the role of media in public life and the maintenance of democracy – both in Sweden and internationally, and how the work is structured in newsrooms.

Photos from the auditorium of the gymnasium, where classes on media production are held.

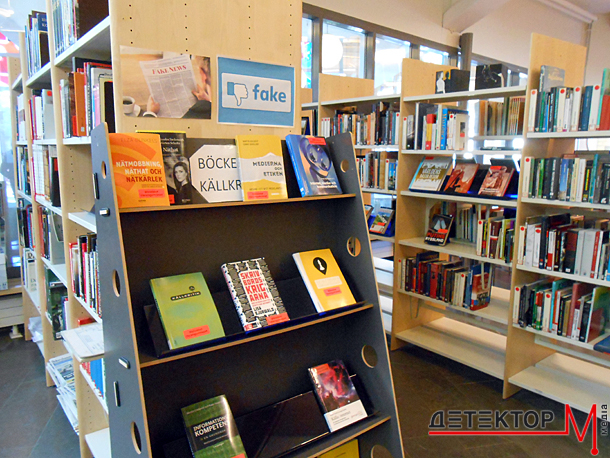

Libraries are an important component of media education. In Sweden, these institutions are valued; according to the norm of 2011, every school must have its own library with a librarian (an exception is possible only if there is a city library in the immediate vicinity of the school).

"When we work with classes, we concentrate on reading skills, criticizing the source of information and searching for information. This is an important skill not only for school work, but also for life as a whole,” says the local employee of the library. "Studying the social sciences, students should be able to develop the ability to seek, critically evaluate and interpret information from different sources, and to assess the relevance and reliability of these sources. We try to teach students how not to reach the stage of frustration and confusion while working on the project, when they are looking for information on a particular topic and it turns out to be too much of it."

***

Of course, in many respects Ukrainian school can not catch up with the Swedish one, including in the field of media literacy. There is a completely different tradition without Soviet history. And, obviously, at times the level of the provision of material needs is higher. But on the other hand, I am glad that recently a large number of Ukrainian teachers have an understanding of the importance of critical thinking and the willingness to immerse themselves in the topic of media. Although this is a very difficult sphere, as Angelina correctly noted: "We face the challenge of preparing our children for the future, which we cannot predict." In my opinion, if we talk about teaching media literacy (and, in general, about the new education), first of all, it is necessary to develop a respectful approach to the student and partner relations in the classroom. When the teacher does not report the only correct answer (this is what actually contradicts critical thinking), but teaches children to raise questions and is genuinely ready to percept their opinion.

Photo by Kateryna Tolokolnikova and Maryna Dorosh