Overview and key findings of the 2023 Digital News Report

In this context, a strong supply of accurate, well-funded, independent journalism remains critical, but in many of the countries covered in our survey, we find these conditions challenged by low levels of trust, declining engagement, and an uncertain business environment.

Our report aims to bring new insights on these issues at what is a particularly difficult time for the industry as well as for many ordinary people. We look in more detail what is behind low engagement and selective news avoidance – and we explore public appetites for approaches that might combat this. More specifically, we look at the sources people use to inform themselves about their personal finances and the extent to which different groups find this type of information easy or difficult to understand.

Our podcast on the report

In the light of the squeeze on household spending, we find that many people have been rethinking how much they can afford to spend on news media. We have conducted detailed qualitative research in the UK, US, and Germany with consumers who have cancelled, maintained, and started subscriptions in the last year to understand the underlying motivations for signing up – as well as key barriers. In our country and market pages, which combine industry developments with local data, we see how different media companies are managing the economic downturn with many accelerating their path to digital by shifting resources further away from broadcast or print.

Perhaps the most striking findings in this year’s report relate to the changing nature of social media, partly characterised by declining engagement with traditional networks such as Facebook and the rise of TikTok and a range of other video-led networks. Yet despite this growing fragmentation of channels, and despite evidence that public disquiet about misinformation and algorithms is at near record highs, our dependence on these intermediaries continues to grow. Our data show, more clearly than ever, how this shift is strongly influenced by habits of the youngest generations, who have grown up with social media and nowadays often pay more attention to influencers or celebrities than they do to journalists, even when it comes to news.

In our extra analysis chapters this year, we’ve identified the most popular news podcasts in around a dozen countries – along with the platforms that are most used to access this content. We also explore increasing levels of criticism of the news media, often driven by politicians and facilitated by social media. We also devote a section to the particular case of public service media that have been at the forefront of this criticism and face particular challenges in delivering their universal mission in a fractious and fragmented media environment.

This twelfth edition of our Digital News Report, which is based on data from six continents and 46 markets, reminds us of the different conditions in which journalism operates in many parts of the world, but also about the common challenges faced by publishers around weak audience engagement and low trust in an age of abundant digital and social media. The overall story is captured in this Executive Summary, followed by chapters containing additional analysis, and then individual country and market pages.

Here is a summary of some of the most important findings from our 2023 research.

-

Our data show how the various shocks of the last few years, including the war in Ukraine and the Coronavirus pandemic, have accelerated structural shifts towards more digital, mobile, and platform-dominated media environments, with further implications for the business models and formats of journalism.

-

Across markets, only around a fifth of respondents (22%) now say they prefer to start their news journeys with a website or app – that’s down 10 percentage points since 2018. Publishers in a few smaller Northern European markets have managed to buck this trend, but younger groups everywhere are showing a weaker connection with news brands’ own websites and apps than previous cohorts – preferring to access news via side-door routes such as social media, search, or mobile aggregators.

-

Facebook remains one of the most-used social networks overall, but its influence on journalism is declining as it shifts its focus away from news. It also faces new challenges from established networks such as YouTube and vibrant youth-focused networks such as TikTok. The Chinese-owned social network reaches 44% of 18–24s across markets and 20% for news. It is growing fastest in parts of Asia-Pacific, Africa, and Latin America.

-

When it comes to news, audiences say they pay more attention to celebrities, influencers, and social media personalities than journalists in networks like TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat. This contrasts sharply with Facebook and Twitter, where news media and journalists are still central to the conversation.

-

Much of the public is sceptical of the algorithms used to select what they see via search engines, social media, and other platforms. Less than a third (30%) say that having stories selected for me on the basis of previous consumption is a good way to get news, 6 percentage points lower than when we last asked the question in 2016. Despite this, on average, users still slightly prefer news selected this way to that chosen by editors or journalists (27%), suggesting that worries about algorithms are part of a wider concern about news and how it is selected.

-

Despite hopes that the internet could widen democratic debate, we find fewer people are now participating in online news than in the recent past. Aggregated across markets, only around a fifth (22%) are now active participators, with around half (47%) not participating in news at all. In the UK and United States, the proportion of active participators have fallen by more than 10 percentage points since 2016. Across countries we find that this group tends to be male, better educated, and more partisan in their political views.

-

Trust in the news has fallen, across markets, by a further 2 percentage points in the last year, reversing – in many countries – the gains made at the height of the Coronavirus pandemic. On average, four in ten of our total sample (40%) say they trust most news most of the time. Finland remains the country with the highest levels of overall trust (69%), while Greece (19%) has the lowest after a year characterised by heated arguments about press freedom and the independence of the media.

-

Public media brands are amongst those with the highest levels of trust in many Northern European countries, but reach has been declining with younger audiences. This is important because we find that those that use these services most frequently are more likely to see them as important personally and for society. These findings suggest that maintaining the breadth of public service reach remains critical for future legitimacy and especially with younger groups.

-

Consumption of traditional media, such as TV and print, continues to fall in most markets, with online and social consumption not making up the gap. Our data show that online consumers are accessing news less frequently than in the past and are also becoming less interested. Despite the political and economic threats facing many people, fewer than half (48%) of our aggregate sample now say they are very or extremely interested in news, down from 63% in 2017.

-

Meanwhile, the proportion of news consumers who say they avoid news, often or sometimes, remains close to all-time highs at 36% across markets. We find that this group splits between (a) those who are trying to periodically avoid all sources of news and (b) those that are trying to specifically restrict their news usage at particular times or for certain topics. News avoiders are more likely to say they are interested in positive or solutions-based journalism and less interested in the big stories of the day.

-

With household budgets under pressure and a significant part of the public satisfied with the news they can access for free, there are signs that the growth in online news payment may be levelling off. Across a basket of 20 richer countries, 17% paid for any online news – the same figure as last year. Norway (39%) has the highest proportion of those paying, with Japan (9%) and the United Kingdom (9%) amongst the lowest. Amongst those cancelling their subscription in the last year, the cost of living or the high price was cited most often as a reason. In the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom, about half of non-subscribers say that nothing could persuade them to pay for online news, with lack of interest or perceived value remaining fundamental obstacles.

-

As in previous years, we find that a large proportion of digital subscriptions go to just a few upmarket national brands – reinforcing the winner takes most dynamics that are often associated with digital media. But in a number of countries, including the United States, we are now seeing the majority of those paying taking out more than one subscription. This reflects the increased supply of discounted offers as well as the introduction of all-access bundles in some markets.

-

Across countries the majority of online users say they still prefer to read the news rather than watch or listen to it. Text provides more speed and control in accessing information, but in a few countries, such as the Philippines and Thailand, respondents now say they prefer video to text. Video news consumption has been growing steadily across markets, with most video content now accessed via third-party platforms such as YouTube and Facebook.

-

News podcasting continues to resonate with educated and younger audiences but remains a minority activity overall. Around a third (34%) access a podcast monthly, with 12% accessing a show relating to news and current affairs. Our research finds that deep dive podcasts, inspired by The Daily from the New York Times, along with extended chat shows, such as The Joe Rogan Experience, are the most widely consumed across markets. We also identify the growing popularity of video-led or hybrid news podcasts.

Changing platforms and the implications for publishers

A running sore for news publishers over the last decade or more has been the increasing influence of tech platforms and other intermediaries on the way news is accessed and monetised. Although search and social media play different roles, news access has for some time been dominated by two giant companies: Google and Facebook (now Meta), who at their height accounted for just under half of online traffic to news sites.1 Although the so-called ‘duopoly’ remains hugely consequential, our report this year shows how this platform position is becoming a little less concentrated in many markets, with more providers competing. The growing popularity of digital audio and video is bringing new platforms into play while some consumers have adopted less toxic and more private messaging networks for communication. In some sense these changes represent a ‘new normal’ where publishers need to navigate an even more complex platform environment in which attention is fragmented, where trust is low, and where participation is even less open and representative.

Gateways to content over time

We continue to monitor the main access points to online news and examine the impact on consumption with different groups. Every year, we see direct access to apps and websites becoming less important and social media becoming more important due to their ubiquity and convenience. At an aggregate level, we reached a tipping point in the last few years, with social media preference (30%) now stretching its lead over direct access (22%).

But these are averages, and there remain substantial differences across countries. News brands in some Northern European markets still have strong direct connections with consumers when it comes to online news, even though platforms are still almost universally used in these markets for a range of other purposes. By contrast, in parts of Asia, Latin America, and Africa, social media is by far the most important gateway, leaving news brands much more dependent on third-party traffic. In other Asia-Pacific markets – such as Japan and Korea – home-grown portals such as Naver and Yahoo! are the primary access points to content, while in India and Indonesia, mobile news aggregators play an important gateway role.

Leaving aside market differences, we also find substantial differences by age group. In almost every case, we find that younger users are less likely to go directly to a news site or app and more likely to use social media or other intermediaries. In analysing this further we find that the annual changes we see in direct vs. social seem to be driven less by older individuals changing their behaviours and more by emerging behaviours of younger groups. The following chart for the UK shows that over-35s (blue line) have hardly changed their access preferences over time, but that the 18–24 group (pink line) has become significantly less likely to use a news website or app. This represents an influx into our survey of more ‘social natives’ who grew up in the age of social and messaging apps, and seem to be displaying very different behaviours as a result.

This reduced dependence on direct access is mirrored by increased use of social media for news. In the UK 41% of 18–24s say social media is now their main source of news, up from 18% in 2015 (43% across markets). These changes are not confined to these so-called ‘social natives’, with some young millennials showing increased dependence on platforms and social media. The problems publishers face in engaging young audiences is only going to get harder over time.

Social network fragmentation

Dependence on social media may be growing, but it is not necessarily the same old networks. Turning to the 12 countries we have been tracking since 2014 we find that in aggregate, Facebook usage for any purpose (57%) is down 8pp since 2017. Instagram (+2pp), TikTok (+3pp), and Telegram (+5pp) are the only networks to have grown in the last year, with much of this coming from younger groups.

Despite Elon Musk’s idiosyncratic stewardship of Twitter, the network’s overall weekly reach remained stable at 22% when our survey was in the field, even if engagement levels may have dipped. There has been no mass exodus to Mastodon, which does not even register in most markets and is used by just 2% in the United States and Germany.

But there have been much more dramatic shifts in the networks used by younger audiences in the last few years. In the following chart, we illustrate how interest in Facebook has waned much faster for under-25s, with attention shifting first to Instagram and Snapchat and now to TikTok. The controversial Chinese-owned app has overtaken Twitter and Snapchat with this group and now has a similar reach to Facebook itself. Other networks such as Discord (15%) and Twitch (12%) are also more widely used by this demographic.

This chart illustrates how attention has shifted, from a few big networks that drove substantial traffic to news websites to a much wider range of apps that require more investment in bespoke content and offer fewer opportunities to post links.

Turning to news usage specifically across all ages, Facebook remains the most important network (aggregated across 12 countries) at 28%, but is now 14 points lower than its 2016 peak (42%). Facebook has been distancing itself from news for some time, reducing the percentage of news stories people see in their feed (3% according to the company’s latest figures from March 2023),2 but in the last year it has also been scaling back on direct payments to publishers and other schemes that supported journalism. The growth of YouTube as a news source is often less noticed, but together with the rise of TikTok demonstrates the shift towards video-led networks.

Although the averages for TikTok are relatively low, usage is much higher with younger groups and in some Asia-Pacific, Latin American, and African countries. It has played a role in spreading both information and misinformation in recent elections in Kenya3 and Brazil4 and has grown strongly in parts of Eastern Europe, where the Ukrainian conflict increased its profile.

The role of news and journalists in different networks

This year we have returned to questions we asked first in 2021 to understand more about where audiences pay attention when using different networks.5 We find that, while mainstream journalists often lead conversations around news in Twitter and Facebook, they struggle to get attention in newer networks like Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok, where personalities, influencers, and ordinary people are often more prominent, even when it comes to conversations around news.

Publishers have been unsure whether and how to adapt their storytelling to these new platforms. As a recent Reuters Institute report on the subject showed (Newman 2022),6 about half of top publishers are now creating content for TikTok, even as others are holding back over concerns about Chinese government influence – as well as the lack of monetisation. But fears about the unchecked spread of misinformation on the platform, and the potential for connecting with hard-to-reach younger audiences, have convinced some news organisations to stake a presence despite the risks.

We’ve also explored for the first time the news topics that resonate in different networks. Again, we find big differences here in terms of audience expectations and interests (see chart below). Twitter users are more likely to pay attention to hard news subjects such as politics and business news than users of other networks, whereas TikTok, Instagram, and Facebook users are slightly more likely to consume fun posts (or satire) that relate to news. It is also striking to note the ambivalence, and possibly fatigue, over the war in Ukraine across all networks. Despite the topic’s importance, we find lower levels of attention when compared with fun news, national politics, or even news about business and economics. It is not clear if this relates to falling interest in general, algorithmic biases, or a mix of the two.

Digging further into the data, we find interesting country and regional differences. TikTok is used much more for political news in Peru, where it has been used by students to organise political protests, as well as in Kenya and Brazil, than it is in the United States, Canada, or Singapore.

Growing scepticism towards algorithms when it comes to news

TikTok’s powerful personalised content feed has refocused attention on the way algorithms can affect our media diets – especially those that deliver ‘more of what you have consumed in the past’. We last looked at public perceptions of such technologies in 2016 when Facebook’s then novel approach to surfacing popular news stories was at its peak.

Since then, we find that people in many countries are less happy about the selection of content both from algorithms and from journalists. These changes are not significant in all markets, but there has been a bigger fall in satisfaction in content-based algorithms amongst younger users (who rely the most on them).

Across ages, the proportion who agree that algorithmically selected news is a good way to get news has shrunk compared to 2016, while the proportion who disagree has stayed roughly the same – meaning that more people now select the neutral middle option. This suggests that for some people a generally positive view of algorithmic news selection has shifted towards ambivalence over time.

The reasons for this change are not entirely clear. We know from last year’s qualitative research that many young people feel overwhelmed by the negative nature of news in their social media feeds. We also know that the imposition of algorithmic instead of pure reverse chronology feeds has caused disquiet amongst a section of the most-heavy social media users in Facebook and more recently in Twitter. In interviews, respondents also frequently express fears that social media may be pushing them down rabbit holes, though this could be related to increased commentary about these issues as much as actual experience. Either way, in this year’s data we find continued high levels of concern that ‘overly personalised’ news could lead to missing out on important information or being exposed to fewer challenging viewpoints (similar to 2016).

Proportion that worry about missing out due to personalisation

Average of selected markets

48%

worry about missing out on important information. 17% don't worry and 35% are neutral.

46%

worry about missing out on challenging viewpoints. 17% don't worry and 37% are neutral.

Q10D_2016b_1/2. To what extent do you agree with the following statement? I worry that more personalised news may mean that I miss out on important information/challenging viewpoints. Base: Total samples in USA, UK, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Belgium, Netherlands, Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, Czech Republic, Poland, Greece, Turkey, Japan, South Korea, Australia, Canada, Brazil = 53,039.

Given lower satisfaction with some algorithmic selection, it is not surprising to find that around 65% of younger users (under-35s) and 55% of older ones (35+) have tried to influence story selection by following or unfollowing, muting or blocking, or changing other settings.

For most people – across ages and countries – the key objective is not to make the feed more fun or more interesting but rather to make it more reliable, less toxic, and with greater diversity of views (see chart below). Yet, despite these clearly stated preferences, social media companies competing for attention and advertising continue to optimise for engagement, with less attention to increasing quality, reliability, or diversity.

None of this means that audiences prefer news selected by journalists and editors, perhaps because many see these traditional sources as also laden with agendas and biases. Indeed, for all the criticism of algorithms, it is notable that content based on previous reading/watching history is still preferred, on average, when compared with selection by journalists across all ages and segments.

Overall, these data highlight general audience dissatisfaction with how content is selected for them – and perhaps an opportunity for publishers to create something better. Many news organisations are now exploring how to mix their editorial judgement and values with algorithms in a way that delivers more relevant, reliable, and valuable content for consumers.

Participation in open networks is declining and becoming less representative

This year we have also explored changes in participation over time in the light of the ongoing reduction in the prominence of news on Facebook and suggestions that engagement may also be reducing in Twitter. Participation was hailed as one of the defining features of Web 2.0 (the social web), breaking with ‘we-publish-you-read’ approaches to journalism – and part of protest movements such as the Arab Spring, #MeToo, and #BlackLivesMatter, amongst others.

We find that many measures of open participation, such as sharing and commenting, have declined across countries, with a minority of active users making most of the noise. Looking back, we can detect a period of peak sharing in some markets between 2016 and 2019, primarily driven by Facebook and by divisive events such as the election of Donald Trump in the United States, the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom, and the vote on Catalan independence in Spain. But since then, online participation has shifted to some extent into closed networks such as WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram, and Discord, where people can have private or semi-private conversations with trusted friends in a less toxic atmosphere.

A further aspect of participation uncovered by our analysis is that a relatively small group of engaged users has a disproportionate influence over political and cultural debates – and that this group has become smaller and more concentrated over time. We have segmented our entire sample into those who actively participate in news by posting and commenting, those who mostly reactively participate by liking and sharing, and those who don’t participate at all, a group that we call passive consumers.

Across markets, only around a fifth (22%) are now active participators, with around half (47%) not participating in news at all. The proportion of active participators has fallen by about 10 percentage points in countries like the UK and United States since 2016. In the UK only around one in ten now actively participates in online news, but their activities often seem to heavily influence the mainstream media agenda and shape wider debates. Across countries we find that this group tends to be male, better educated, and more partisan in their political views in almost every country – the same, unrepresentative demographic profile many news media cater to.

The group that participates in news has always been different from the general population, but these data suggest that online participation may have become more influenced by unrepresentative politically committed groups over the last few years as mainstream users disconnect or move some of their discussions to more private spaces. Publishers need to be aware of these changes and find ways to broaden and deepen engagement with the more passive or reactive majority.

Misinformation and disinformation

The platform changes we have described, including the switch of attention to new networks, do not seem to be lessening public fears about misinformation and disinformation. Across markets, well over half (56%) say they worry about identifying the difference between what is real and fake on the internet when it comes to news – up 2 percentage points on last year. Those who say they mainly use social media as a source of news are much more worried (64%) than people who don’t use it at all (50%) while many countries with the highest levels of concern also tend to have high levels of social media news use. This is not to say that social media use causes misinformation, but documented problems on these platforms and greater exposure to a wider range of sources does seem to have an impact on how confident people feel about the information they come across.

When looking at the types of misinformation that people claim to see, we find that dubious health claims around COVID-19, including from anti-vaccination groups, are still widespread, along with false or misleading information about politics. In Slovakia, one of the countries bordering Ukraine, almost half of our sample said they had seen misinformation about the Ukraine conflict in the previous week, around twice the proportion that said this in the UK, United States, or Japan.

Levels of perceived misinformation around climate change are around three times higher in the United States (35%) than they are in Japan (12%). Some prominent politicians, opinion writers in the media, and groups aligned with fossil fuel interests continue to disregard the scientific consensus and belittle green policies. Environmental groups say climate change denialism has been making a ‘stark comeback’ on social media, with misleading advertisements on Facebook and other networks and viral hashtags such as #climatescam on Twitter, which critics say has been failing to properly moderate harmful content since the takeover by Elon Musk.7

Platform shifts summarised

Taken together, what are we to make of these changes in the platform environment? Our reliance on social media continues to grow, but a growing variety of different platforms now competes to serve different purposes in our lives, with news often becoming less central to how they work. At the same time, we seem to be less happy about the way news content is surfaced (algorithms), the accuracy of the content (misinformation), and the quality of debate (participation). Newer platforms like Instagram and TikTok, with more visual content, are optimised better for younger users, but they often require more bespoke investment from publishers with little return in terms of traffic or revenue. With further innovation on the way, fuelled by artificial intelligence (AI) and automation, publishers will need to be more focused than ever on defining how these intermediaries can help drive new users and deeper connections whilst contributing to their core businesses.

Business pressures grow amid downturn, subscriptions stall

Our country pages this year are full of stories of industry cost-cutting, journalistic layoffs and the slimming down (or closure) of print editions due to a combination of rising costs and lower than expected advertising revenues. These pressures – along with the decline in traffic from social networks such as Facebook and Twitter – have also affected digital born brands, with the closure of BuzzFeed News and Vice Media filing for bankruptcy. These companies had pioneered a model of ad-supported, socially optimised news that had at one stage threatened to upend the industry.

Against this background, it is not surprising that many traditional publishers have been trying to refocus on recurring reader revenue models such as subscription and membership. These approaches have been a rare industry bright spot over the last few years, with upmarket newspaper brands such as the New York Times now attracting more than 6 million digital-only subscribers to its news products alone.8

The Digital News Report has been tracking the proportion paying for online news for almost a decade in the richer, newspaper-centric countries that have been leading this trend. We do not report subscription numbers in African countries, India, or a few other markets where we feel the sample is not sufficiently representative. As in previous years, we have focused our reporting on a basket of 20 countries where publishers have been most active and where the concept of paying for online news is well understood.

In these markets, the average proportion making any online news payment has remained at 17% for the second year in a row – raising questions about whether we may have, for now, reached the peak of the subscription trend, at least for current subscription offers. There are statistically significant falls in Belgium (-4) and Canada (-4) and a rise in Australia (+4) but otherwise there is little movement in headline rates compared with last year, and our over-time chart (below) seems to confirm a levelling off process underway. The countries with the biggest proportion paying for news, with the exception of the United States, tend to be smaller markets with a high concentration of publishers, most of which introduced paywalls around the same time.

As in previous years, a winner takes most dynamic persists in many markets. In Finland half of all ongoing online news subscribers (53%) pay for Helsingin Sanomat, the country’s paper of record. In the United States, the New York Times (36% of ongoing subscribers) has stretched its lead over the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal and is building a significant subscription base in other English-speaking markets such as Canada and Ireland. Elsewhere we find subscriptions are primarily national and tend to be widely spread across a range of publications.

In most countries, the majority of subscribers only pay for one publication, but in the United States around half (56%) pay for two or more – often a national and local paper combination. Other second subscriptions include political and cultural magazines such as the Atlantic and the New Yorker, partisan digital outlets such as the Epoch Times and passion-based titles such as the Athletic. We also see growing levels of payment for platform-based news subscription products such as Apple News+ (18% of US subscribers). We have started to see more second subscriptions in other markets including Australia, Spain, and France, perhaps due to the greater availability of low-price trial offers.

In the United States 8% of subscribers pay for a newsletter written by an individual journalist or influencer and 5% pay for a podcaster or YouTuber. This trend is still largely confined to the US.

The impact of the cost-of-living crisis on news subscriptions

Although headline levels are largely unchanged, we find a large amount of underlying change, much of it driven by cost pressures. Around one in five news subscribers (23% on average) say they have cancelled at least one of their ongoing news publications, while a similar number say they have negotiated a cheaper price (23%) At the same time, others have taken up new subscriptions, often using a cheap trial offer. Given the relatively small number of respondents these findings are based on, and the very real variation from publisher to publisher and market to market, the findings cannot necessarily be generalised, but they clearly show that, while the headline number of subscribers have stayed the same, there is often a considerable amount of churn at a title level.

Across countries, however, the underlying reason for cancelling was that people simply weren’t using the subscription enough to justify the cost or they didn’t have enough time. At a fundamental level, news media that struggle to get people to pay attention to them will have an even harder time convincing people to pay.

As with TV streaming subscriptions, we found widespread juggling of trials and special offers to reduce outgoings. But for many the jump from a trial to a full-price subscription was a critical time to reflect on the value.

According to our data, around half of subscribers are maintained subscribers, who are confident about value and are unlikely to churn. These tend to be older and less price-sensitive customers. But that leaves a significant proportion of price-sensitive subscribers who are shopping around for deals and regularly reassessing value. This suggests that churn is likely to be a major problem this year and beyond.

Reasons to subscribe to a news publication

Across markets, the most important stated reason to subscribe is to get access to better quality or more distinctive journalism (51% on average, 65% in the US) than can be obtained for free. A second reason, which is particularly prevalent in the United States, is to help fund good journalism, perhaps because European consumers feel they have already paid for this though their taxes or public media licence fees. Identification with the brand and its politics is a very important reason to subscribe in the UK and US, but much less important in Germany. Finally, games and member benefits are important factors for some, along with a good user experience for the website and app.

This year we wanted to explore more about those who do not currently pay for online news across our 20 markets to see if there was anything that could persuade them to do so. Encouragingly, some said they might pay if the content was more distinctive (22%), if there was an ad-free option (13%) or if the price was cheaper or provided more flexibility (32%). On the other hand, many more people (42%) said that nothing would persuade them to pay – as many as 65% of current non-payers in the UK and 54% in Germany.

Proportion of non-subscribers that say each would most encourage them to pay

Average of selected countries

-

More valuable content

22%

Especially younger and more interested groups

-

Ad-free

13%

-

Cheaper/flexible

32%

Especially younger and more interested groups

-

Nothing

42%

65% in UK | 54% in Germany | 49% in the USA [especially older and less interested groups]

Q4_Pay_2023. You say you don’t currently subscribe or donate to an online newspaper or other news service. Which of the following, if any, would most encourage you to pay? Please select all that apply. Base: Those that don’t subscribe to online news in USA, UK, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Belgium, Netherlands, Switzerland, Austria, Poland, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Canada = 33,460.

Overall, the biggest opportunity to attract new subscribers lies in reducing the price, for example with special offer trials, or differential pricing, but this also carries significant risks around long-term profitability.

More flexibility is another theme that came out strongly in our qualitative work as well as our survey. Many potential subscribers, especially younger people, do not want to be ‘tied down’ by one subscription. Instead, they want to access multiple brands with little or no friction for a fair price.

Schibsted in Norway now offers six national and local newspapers, 44 magazines, and exclusive podcasts in its all-access package, which costs just a bit more than a single publication subscription. Amedia offers more than one hundred titles including local, premium sports and podcasts in its +Alt subscription (right). It is early days, but this bundle has been taken up by 4% of ongoing subscribers in Norway, according to our latest data, and we see emerging examples in other Nordic and Benelux markets.

Our detailed research this year across markets highlights how important news subscriptions are to some, but also how fragile the arrangement is for others. In countries such as the UK and US, many people subscribe based on either a long-standing relationship, or the sense that the outlet speaks to them and speaks for them. This brand identification is closely linked to the content itself, raising questions about whether paid models may encourage more partisan editorial approaches.

Beyond this, respondents need to believe they are getting value for money, especially in the current economic climate. They also need to be sure that the content is exclusive, curated, and that it is unavailable for free. But they do not want to pay over the odds. Larger, more expensive bundles appeal to those already interested in news, but may be less attractive to many casual news users.

Economic downturn and the role of the media

The current economic crisis, which has brought rampant inflation, job insecurity, and rising levels of poverty, has affected the vast majority. Across markets, three-quarters (77%) of people say they have been affected a great deal or somewhat by the cost-of-living crisis, with only a fifth (20%) saying they have been largely unaffected. Our data show that over half (52%) turn to mainstream media or specialist sources for information about personal finances and/or the economy, with social media personalities and creators (12%) playing a relatively minor role. This reinforces previous data showing that traditional media play a more important role when times get tough.

But as with other media topics we have explored in the past, we find that younger groups are much more likely to rely on social media and influencers compared with over-55s. They are less likely to pay attention to mainstream media on finance topics. Family and friends are also seen as a key source of information by young and old.

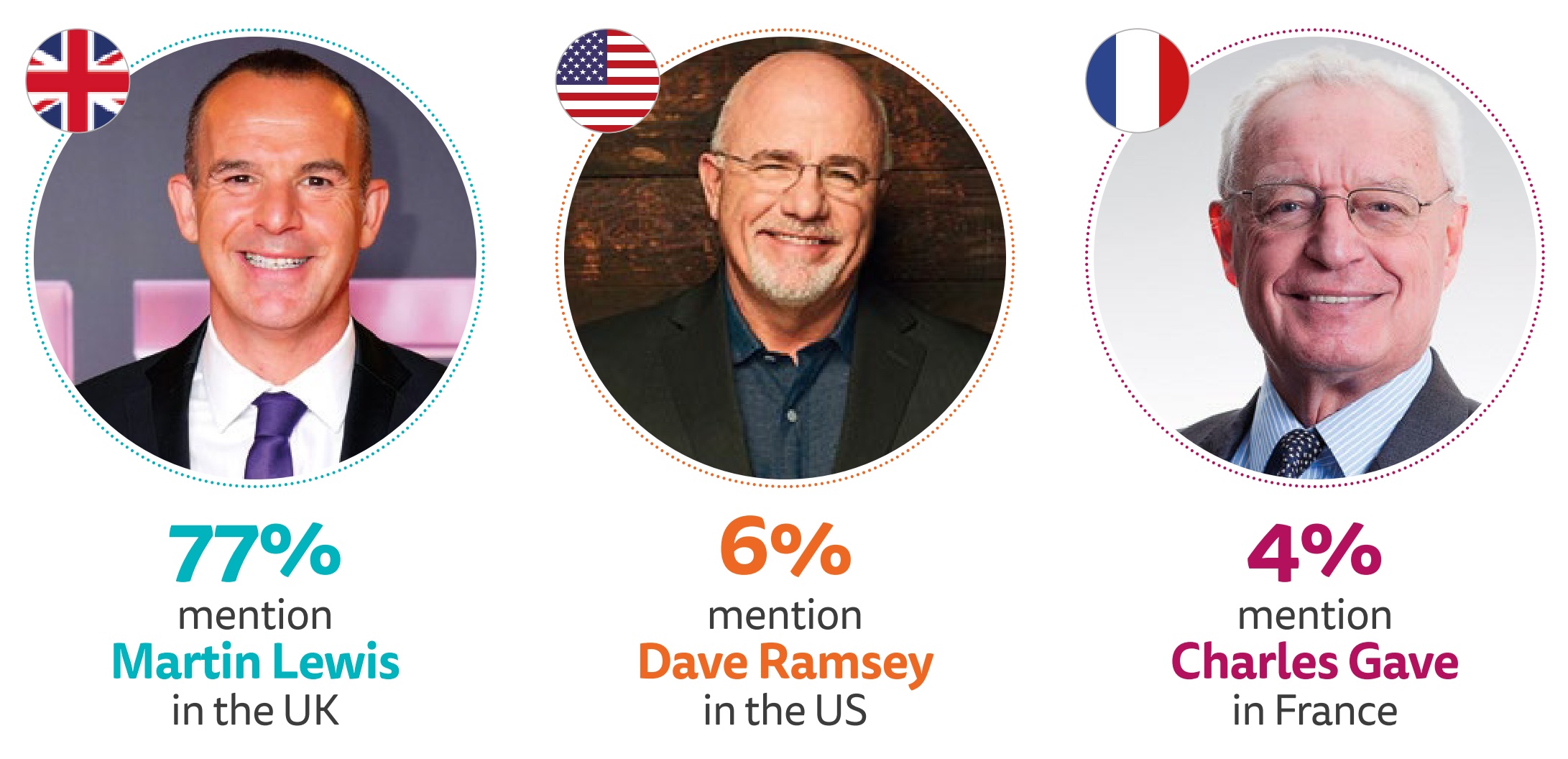

In some countries, personal finance experts who often run their own websites or channels are building significant followings. In the UK, for example, the founder of moneysavingexpert.com, Martin Lewis, has become a household name – dispensing practical advice on how to make money go further as well as lobbying the government for policy changes. But it is important to note that, as a result of his engaging personality, he has been commissioned to present mainstream shows on television and radio as well as his own podcasts and newsletters. The following pictures highlight some of the other (mainly male) independent experts who have built a personal following across channels including social media.

Proportion that pay attention to independent finance experts that named each

Selected countries

Finance_Open_2023. You say that you pay a lot of attention to experts with an independent public profile (e.g. their own social channels or TV shows) for news or information related to your personal finances and the wider economy. Who do you pay attention to? Base: All that say they pay attention to experts in UK = 510, USA = 425, France = 349. Note: Open-ended question. Respondents could type in up to three names.

Although people rely greatly on mainstream media for finance and economic news, a significant proportion say they find it difficult to understand. This is especially true for people who need the information most. Overall, around a third (30%) found it difficult, with those most affected by the cost-of-living crisis, women, and those with lower income and education levels finding the news more difficult both to understand and to apply in their daily lives.

Interest in news continues to decline, fuelling disengagement and selective news avoidance

Unlike the COVID-19 pandemic, neither the cost-of-living crisis nor the ongoing Ukraine war has led to a sustained upsurge of news consumption. Across a large group of countries, our survey data show a decline in weekly consumption across different news sources over the last year and lower interest in the news overall (see next chart). Self-declared interest in news is lower amongst women and younger people, with the falls often greatest in countries characterised by high levels of political polarisation. Some markets, with stable, well-funded media and high trust in institutions, such as Finland and the Netherlands, seem to have largely bucked the trend, while previously stable markets such as Austria and Germany are starting to be affected.

Proportion that say they are very or extremely interested in news over time – Selected countries

Countries with big declines

Countries with more stable levels

These declines in news interest are reflected in lower consumption of both traditional and online media sources in most cases. The proportion that say they did not consume any news in the last week from traditional or online sources (TV, radio, print, online, or social media) has increased again this year across countries. The highest proportion of ‘disconnected’ users can be found in Japan (17%), the United States (12%), Germany and the UK (9% each). But in countries like Finland (2%) a much smaller proportion are disengaged.

Addressing selective news avoidance

Last year’s report highlighted the problem of selective news avoidance, especially with some hard-to-reach groups. Publishers have spoken openly about falling web traffic and the difficulty of engaging audiences with subjects such as the war in Ukraine and climate change.9 Our data provoked much debate about the precise nature of news avoidance and this year we have explored this further, as well as looking at what can be done to address it. In this year’s data we find continued high levels of selective avoidance (people who say they actively do it sometimes or often), with the headline rate at 36%, 7 percentage points above the figure in 2017 but two points lower than last year. It was down in the UK and Brazil but up some other countries, such as Greece, Bulgaria, and Poland.

This year, for the first time, we asked about the different ways that people avoid the news and found that around half of avoiders (53%) were trying to do so in a broad-brush or periodic way – for example, by turning off the radio when the news came on, or by scrolling past the news in social media. This group includes many younger people and those with lower levels of education.

A second group tends to avoid news by taking more specific actions. This may involve checking the news less often (52% of avoiders), for example by turning off mobile notifications, or not checking the news last thing at night, or by avoiding certain news topics (32% of avoiders) such as the war in Ukraine or news about national politics.

Proportion of news avoiders that say they do each

All markets

53%

of avoiders avoid most sources. e.g. scrolling past news, changing channels when news comes on.

52%

of avoiders check sources less often. e.g. limit to certain times of day, turning off notifications, etc.

32%

of avoiders avoid some topics. e.g. topics that bring down mood or increase anxiety.

Avoidance_behaviours_2023. You said that you try to actively avoid news. Which of the following, if any, do you do? Please select all that apply. Base: Those who sometimes or often avoid the news in all markets = 33,469.

In our qualitative study this year we’ve heard more evidence about the circumstances that give rise to this selective news avoidance, even by those who are otherwise very interested. Certain news stories that are repeated excessively or are felt to be ‘emotionally draining’ are often passed over in favour of something more uplifting.

Avoidance of the war in Ukraine is widespread

Amongst avoiders, almost four in ten (39%) said they had avoided news on the war in Ukraine, followed by national politics (38%), issues around social justice (31%), news about crime (30%), and celebrity news (28%). Selective avoidance of Ukraine news was highest in many of the countries closest to the conflict, reinforcing findings from our additional survey last year, soon after the war had begun.10

Our data may not suggest a lack of interest in Ukraine from nearby countries but rather a desire to manage time or protect mental health from the very real horrors of war. It may also be that consumers in these countries already consider themselves to be well-enough informed on Ukraine, with extensive and detailed coverage across all channels, including via social media.

Bitter political debates are another key factor driving avoidance

Comparing Finland with a politically polarised country such as the United States (see next chart) that is less affected by the war, we find a very different pattern of topic avoidance. In the United States, we find that consumers are more likely to avoid subjects such as national politics and social justice, where debates over issues such as gender, sexuality, and race have become highly politicised. By contrast, there is very little active avoidance of local news in either country.

For some people, bitter and divisive political debates are a reason to turn off news altogether, but for some political partisans, avoidance is often about blocking out perspectives you don’t want to hear. When splitting topic-based avoidance by political orientation, we find those on the right in the United States are five times more likely to actively avoid news about climate change than those on the left and three times more likely to avoid news about social justice issues such as gender and race. Those on the left are more likely than those on the right to avoid news about crime or business and finance.

Addressing news avoidance

Evidence that some people are turning away from important news subjects, like the war in Ukraine, national politics, and even climate change is extremely challenging for the news industry and for those who believe the news media have a critical role in informing the public as part of a healthy democracy.

Many news organisations are looking to tackle both periodic and specific avoidance in a variety of ways. Some are looking to make news more accessible for hard-to-reach groups, broadening the news agenda, commissioning more inspiring or positive news, or embracing constructive or solutions journalism that give people a sense of hope or personal agency. In our survey this year, we asked respondents about their interest in these different approaches.

At a headline level, we find that avoiders are much less interested in the latest twists and turns of the big news stories of the day (35%), compared with those that never avoid (62%). This explains why stories like Ukraine or national politics perform well with news regulars but can at the same time turn less interested users away. Selective avoiders are less interested in all types of news than non-avoiders but in relative terms they do seem to be more interested in positive or solutions-based news. Having said that, it is not clear that audiences think much about publisher definitions of terms such as positive or solutions journalism. Rather we can interpret this as an oft-stated desire for the news to be a bit less depressing and a bit easier to understand.

There are no simple solutions to what is a multifaceted story of disconnection and low engagement in a high-choice digital environment, but our data suggest that less sensationalist, less negative, and more explanatory approaches might help, especially with those who have low interest in news. Of course, what people say doesn’t always match what they do, and other research reminds us that in practice we are often drawn towards more negative and emotionally triggering news (Robertson et al. 2023).11 This may be true in the moment, but over time it seems to be leaving many people empty and less satisfied, which may be undermining our connection with and trust in the news.

Trust in the news continues on a downward path with notable exceptions

Across markets, overall trust in news (40%) and trust in the sources people use themselves (46%) are down by a further 2 percentage points this year. As in previous years, we find the highest trust levels in countries such as Finland (69%) and Portugal (58%), with lower trust levels in countries with higher degrees of political polarisation such as the United States (32%), Argentina (30%), Hungary (25%), and Greece (19%).

However, the United States has seen a 6pp increase in news trust in the last year as politics has become a bit less divisive under Joe Biden’s presidency. Meanwhile, trust in Greece is now the lowest in our survey amid heated discussions about press freedom and a wiretapping scandal involving prominent politicians, businessmen, and journalists.

Germany has also seen a significant fall in trust in the news (-7pp) in the wake of a new government, concerns about energy security, and the war in Ukraine, though a closer examination shows the number essentially returning to pre-COVID-19 levels. Indeed, through the rear-view mirror, the COVID-19 trust bump is clearly visible in the following chart, though the direction of travel afterwards has been mixed. In some cases (e.g. Finland), the trust increase has been maintained, while in others the upturn looks more like a blip in a story of continued long-term decline. As always, it is important to underline that our data are based on people’s perceptions of how trustworthy the media, or individual news brands, are. These scores are aggregates of subjective opinions, not an objective measure of underlying trustworthiness, and changes are often at least as much about political and social factors as narrowly about the news itself.

Media criticism and its impact on trust

One potential contributing factor to low trust has been widespread and forthright criticism of the news media from a range of different sources. Digital and social media have provided much-needed accountability for news media, with articles and commentaries scrutinised for accuracy, hypocrisy, and bias. But other criticisms are less fair, coloured by political agendas and often forthrightly expressed by activists or special interest groups. Political polarisation hasn’t helped, and many of our country pages carry examples of verbal abuse, coordinated harassment of individual journalists and independent media, and, in some cases, physical attacks against journalists. Looking across our entire dataset, we find a correlation between low trust and media criticism. Some of the highest reported levels of media criticism are found in countries with highest levels of distrust, such as Greece, the Philippines, the United States, France, and the United Kingdom. The lowest levels of media criticism are often in those with higher levels of trust, such as Finland, Norway, Denmark, and Japan.

On average, politicians are most often cited by respondents for their criticisms of the media, followed by ordinary people. This is particularly the case in the United States (58%), where some leading politicians regularly deploy phrases like ‘fake news media’ to deflect accountability reporting and mobilise loyalists. Commentators on politically polarised cable TV outlets also routinely attack other news organisations with media-critical segments.

Politicians and activists are seen as a main source of media criticism in the Philippines (46%), where journalists critical of the government are routinely branded communists or terrorists. In Mexico, President López Obrador, known as AMLO, carries a section in his morning news conferences where he routinely exposes so-called ‘fake stories’ published by the mainstream press.

In terms of where people see or hear media criticism, we find social media (49%) cited most often, followed by chats with people offline (36%) and then other media outlets (35%) such as television and radio. The bad-mouthing of journalists is not new, but attacks can now be amplified more quickly than ever before through a variety of digital and social channels in ways that are often closely coordinated, sometimes paid for, and lacking in transparency. Media criticism has become a key part of the political playbook, a way to deflect criticism and intimidate investigations – and these tactics often land on fertile ground.

Public service news media under pressure

In recent years, public service media (PSM) have been one of the objects of media criticism, often from politicians, activists, and alternative media on the right, but also from commercial media who feel they provide unfair competition in the digital world. Increasingly polarised debates have made it harder to deliver news services that are seen to be impartial by all parts of society, while falling reach for traditional broadcast services has increased pressure on funding models whose justification is the provision of universal services.

In the last year, Austria’s public broadcaster, ORF, has been ordered to cut over €300m by 2026 as the government looks set to change its funding model. In the UK, the BBC has merged its global and national 24-hour news channels after a licence fee freeze and has faced a new crisis over impartiality. A corruption scandal in Germany has undermined confidence in public media there, and the Swiss public broadcaster, SRG SSR, is due to face a new referendum which will propose major funding reductions. Against this background, we wanted to get a sense of how important audiences still feel public media news is for them and for society. We have focused on around 20 public media organisations in Western Europe and Asia-Pacific that are generally seen as being relatively independent of government.

In almost every country covered, more people say public service media are important than unimportant. It is little surprise that the perceived importance is highest in Nordic countries, small territories with a unique language and culture to protect, and public service media that many observers regard as among the best at delivering on their remit in a changing media environment. Public news broadcasters are seen as less important in Southern Europe, though their importance to society is rated a few points higher in every country.

Our research suggests that the experience of using public service media is a powerful driver of how important people think they are. Independent public media are still often the first port of call for all age groups when looking for reliable news around stories such as the Ukraine conflict or COVID-19 but in almost all cases online reach is still much lower than that achieved through television and radio. In Germany and the UK, younger audiences are less likely than older ones to use public broadcasters and this is reflected in our scores around importance. In Germany, over-55s find news from public service media (ARD and ZDF) much more important than all other age groups. In the UK this sense of importance is a bit more evenly spread across age groups.

We find similar gaps elsewhere, with a weaker sense of importance among those with lower levels of education, despite an explicit remit around providing for underserved audiences. Those who self-identify on the political right are also, in most cases, much less inclined to rate public media important compared with those on the left – making it easier for opponents to make the case that these organisations are part of a ‘liberal elite’.

Further detailed analysis, where we also control for usage, suggests that education and political orientation remain significant predictors of people’s perception of public service media news, but this is not the case with age. These findings suggest that lower perceived importance of public service media among younger people is related more to the fact that many younger people have grown up preferring digital and social media, and have little or no experience of using these services. This underlines how important it is for their long-term legitimacy that public service media find better ways to reach young people with relevant content and formats.

The growing importance of multimedia formats in online news

This year we asked respondents about their preferences for text, audio and video when consuming news online. On average, we find that the majority still prefer to read the news (57%), rather than watch (30%) or listen to it (13%), but younger people (under-35s) are more likely to listen (17%) than older groups. In the past, young and old have told us that they find reading the quickest and easiest way to access information, but the opportunity to multitask by listening to news seems to be particularly appealing to those brought up with smartphones and headphones.

Behind the averages we find significant and surprising country differences. In markets with a strong reading tradition, such as Finland and the United Kingdom, around eight in ten still prefer to read online news, but in India and Thailand, around four in ten (40%) say they prefer to watch news online, and in the Philippines that proportion is over half (52%). It is worth bearing in mind that less representative samples in these countries may be a factor in these differences.

In many Asian countries, populations tend to be younger, mobile data tend to be relatively cheap, and video news is widely available via platforms such as YouTube and TikTok. In Thailand, for example, greater opportunities for freedom of expression online have led to the creation of a spate of independent TV-style online shows that are widely consumed on mobile phones.

But even in countries with strong reading preferences, we find different patterns with younger generations. In the UK, a majority of 18–24s still prefer text, but they are much less likely to want to read online news compared with older groups, and have a stronger preference to watch as well as listen, suggesting future online news habits may look very different in the next decade.

Video consumption has been growing across markets

Overall, we find that weekly consumption maps strongly onto these underlying preferences. In Kenya (97%), the Philippines (94%), and Thailand (91%), for example, respondents are twice as likely to consume news video weekly as those in the UK (46%) or Germany (45%).

Across all markets, almost two-thirds (62%) consumed video via social media in the previous week and just 28% when browsing a news website or app. Facebook and YouTube remain the biggest outlets for online video, but with under-35s TikTok is now not far behind.

Younger groups consume disproportionately more news video via social networks, but are less likely to access video via news websites or apps. The next chart illustrates how 18–24s have leaned into social media consumption in the last few years, a period that has coincided with the rise of short TikTok videos, Instagram Reels, and YouTube Shorts.

Podcast reach remains stable with a loyal audience

Audio news consumption has been growing in recent years driven by changing underlying audience preferences, higher quality content, and better monetisation. Publishers have been investing in podcasts because they are relatively low cost, help build loyal relationships, and are good at attracting younger audiences. Public broadcasters and leading newspaper publishers such as the New York Times and Schibsted in the Nordic region have invested in original shows – as well as building their own platforms for distribution. Overall, our data show that around a third (34%) access a podcast monthly across a basket of 20 countries where the term podcast is well understood. Around a third of these (12%) access a news podcast regularly, with the strongest growth in the United States and Australia. Just under a third (29%) say they have spent more time listening to podcasts this year, with 19% saying they have listened less.

News makes up a relatively small proportion of podcasts in most markets, but plays a bigger role in the United States (19%). By contrast, only around 8% listen to news podcasts monthly in the UK. This year, we asked respondents in 12 countries to tell us which news podcasts they listened to, using an open survey field, and this has enabled us to build a good picture of the different types as well as their relative popularity.

In the United States, we find the New York Times explanatory podcast The Daily to be the most widely listened-to show, and the format has been widely copied around the world. The Danish equivalent, Genstart, was mentioned by 24% of news podcast listeners there, with public broadcaster DR accounting for over half of all named podcasts – and it is a similar story in Norway. In other countries, however, there are no clear winners, with a large number of podcasts each attracting a relatively small audience.

Extended talk formats such as The Joe Rogan Experience, which is exclusive to Spotify, are also popular with news podcast users across the world, even though shows can last up to several hours. In the UK, the BBC’s Newscast faces stiff competition from Global Radio’s The News Agents and political talk show The Rest Is Politics. The production of podcasts is also becoming more complex, we find, with many shows now filmed to enable wider distribution via video platforms such as YouTube, as well as more impactful promotion via social media.

Conclusions

While some individual news brands have been very successful at building online reach or even convincing people to subscribe, this year’s data show how fragile these advances are in the face of economic and political uncertainty, fragmenting audiences, and a new wave of platform disruption. Even as a few winners are doing well in a challenging environment, many publishers are struggling to convince people that their news is worth paying attention to, let alone paying for.

In the short term, growth is severely challenged by the combined impact of rising costs and falling revenues, as well as increasingly unpredictable traffic from legacy social networks like Facebook and Twitter. In the longer term, our data suggest that significant shifts in audience behaviour, driven by younger demographics, are likely to kick in, including a preference for more accessible, informal, and entertaining news formats, often delivered by influencers rather than journalists, and consumed within platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok. Visual and audio formats won’t replace text online, but they are set to become a more important part of the mix over the next decade. But across formats, we still see the convenience and aggregating power of platforms trumping direct access, even if some smaller countries with strong publishers and high levels of trust have been able to buck these trends.

With an abundance of channels and options now available to consumers, it’s perhaps not surprising that we find that news consumers are increasingly overwhelmed and confused, with many turning away temporarily or permanently. Selective news avoidance and news fatigue has been exacerbated by the tough times that we are living through. The ‘public connection’ between journalism and much of the audience continues to fray.

In this context is clear than most consumers are looking not for more news, but news that feels more relevant, and helps them make sense of the complex issues facing us all. New technological disruption from Artificial Intelligence (AI) is just around the corner, threatening to release a further wave of personalised, but potentially unreliable content.

Against this background, it will be more important than ever for journalism to stand out in terms of its accuracy, its utility, and its humanity. We can see from our data this year that audiences are ambivalent about algorithms but they are still not convinced that journalists and news organisations can do any better in curating or summarising the most important developments. The challenge ahead is, more than ever, about restoring relevance and trust through meeting the needs of specific audiences. Building relationships and communities won’t be all about pushing people to websites and apps, even though that remains important for business models, but it will also mean reaching out through other platforms and channels with trusted information that provides real value to consumers – in return for attribution and hopefully financial return.

The war in Ukraine and the consequent economic shocks have encouraged publishers to further accelerate their transition to digital, embracing new business models, different types of storytelling, and new forms of distribution too. There will be many different paths but innovation, flexibility, and a relentless audience focus will be some of the key ingredients for success.

Footnotes

1 According to the online measurement site Parse.ly, which tracked aggregate data on referral traffic based on publishers in their network.

5 In 2021 we only gave respondents one option but in 2023 we allowed multiple options to be selected so the data are not directly comparable.

6 More on our report on TikTok.

9 72% of industry executives said they were worried or very worried about avoidance in Journalism and Technology Predictions 2023 (Newman 2023).

10 Read the chapter on Ukraine in the Digital News Report 2022.

11 Negativity drives online news consumption (Robertson et al. 2023).