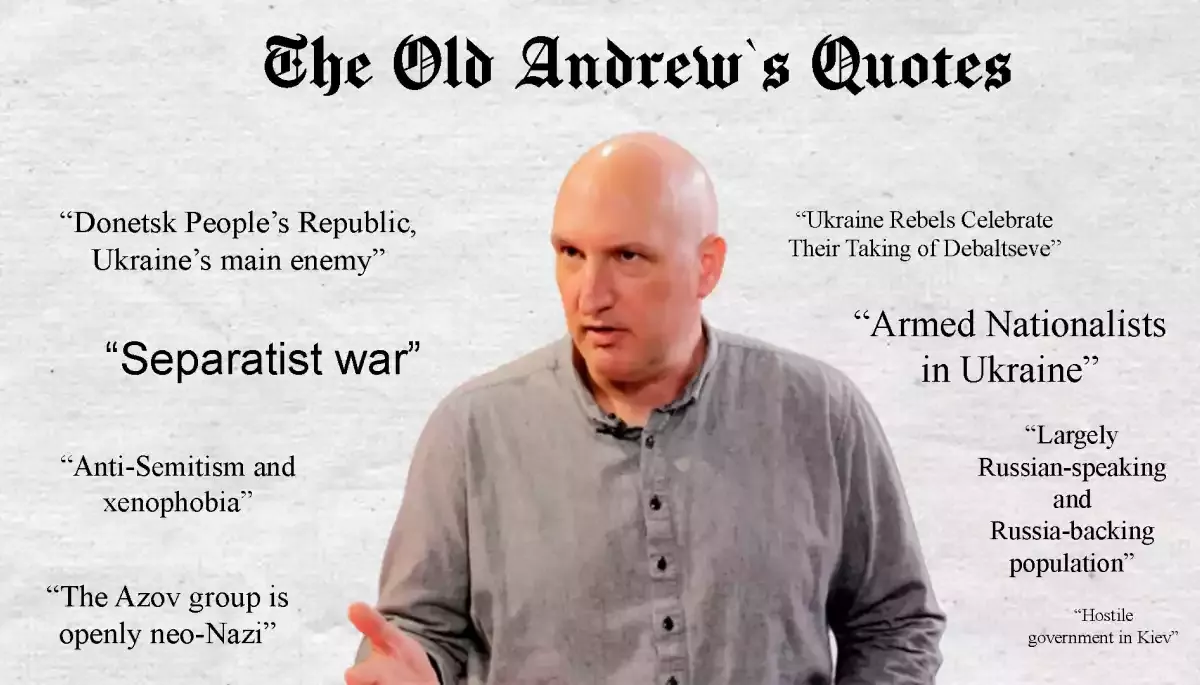

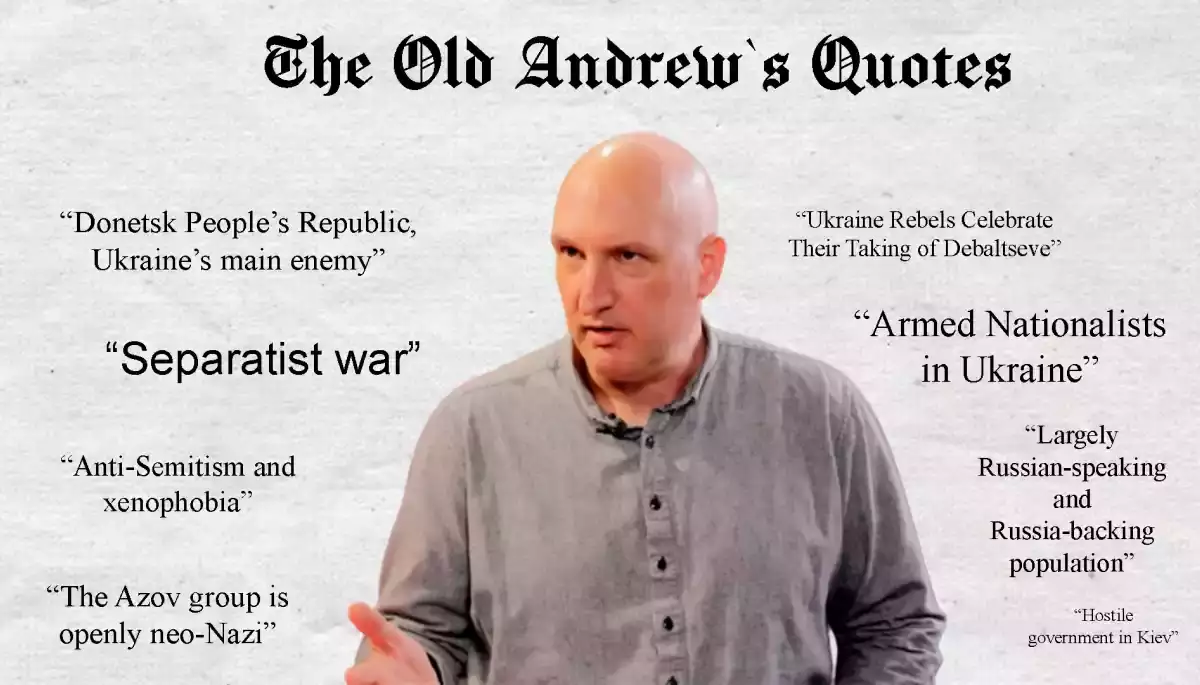

Civil war and nationalists. Things Andrew Kramer has been writing about Ukraine

Civil war and nationalists. Things Andrew Kramer has been writing about Ukraine

Українською текст читайте тут.

"Even as the president of Ukraine insisted that Putin was bluffing, Andrew Kramer was on the ground getting ready for war," – so began the text of The New York Times’ announcement on the appointment of the head of the newly established Ukraine bureau. The post was given to Andrew Kramer, a media professional who has been working at The Times since 2005 – and whom Ukrainians have many issues with. For one thing, not every Western journalist got vaccinated with the Russian "Sputnik V" vaccine to demonstrate its safety and availability.

Also, not every media outlet is as influential as The New York Times is. Personal views of Andrew, who is presented from the very outset to be better informed than the president of the state, are going to impact our country’s image in the world. Thus, "Detector Media" has decided to read what the journalist has been writing about Ukraine.

To start with, one should know that Andrew Kramer worked at the Russia bureau of The New York Times for almost ten years. According to the outlet, "for years he was the primary reporter covering Ukraine from his perch in the Moscow bureau." That is exactly how Kramer’s materials from that time look like: the journalist mentioned our country mostly in the context of Russia. For instance, this was the case with the gas conflict of 2008-2009. A material on the suspension of gas supplies reads that there are claims from both sides, but only Moscow's arguments are elaborated upon. Moreover, the text contains Putin's accusation that Ukraine is stealing gas, yet no comment from the Ukrainian side is included with regard to that matter. Until 2013, Kramer had all but one material in which he focused on Ukraine and did not mention Russia: it had to do with Gongadze’s murder.

With the beginning of the Revolution of Dignity, events in Kyiv start attracting Kramer’s attention more and more. In one of his articles, he writes about the All-Ukrainian Union "Svoboda": "the party won 8.5 percent of the seats in Parliament, provoking warnings from Israel about rising anti-Semitism and xenophobia in Ukraine, a country with a rich history of both." It remains unclear how Kramer came to that conclusion – the article contains no respective arguments.

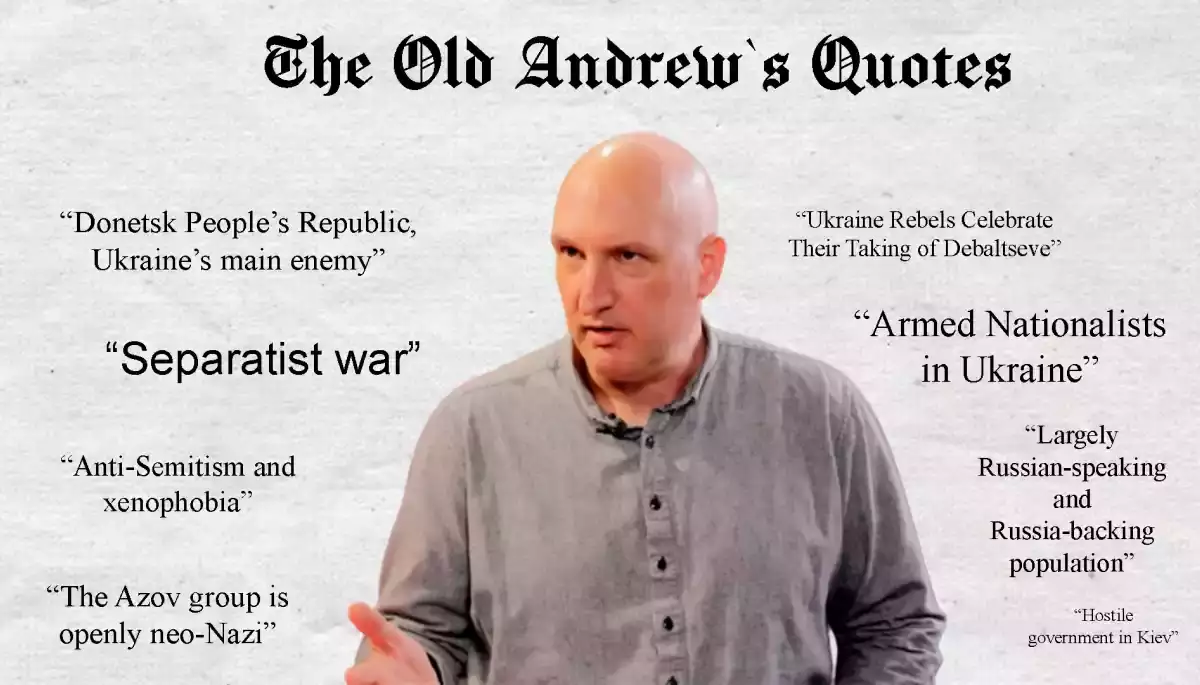

Later, the war with Russia starts in Ukraine, and a career of a war correspondent starts for The New York Times’ journalist. Andrew writes that the occupants rewrite the history of the Holodomor; that Russia manipulates the photo of the downed Boeing; that the Kremlin uses its troops in Ukraine’s east. However, there is a big catch: for Andrew Kramer, the war itself still is a civil one, since Russia is not the other party to it, but rather "Russian-backed separatists" or "rebels" are.

Andrew Kramer was one of the journalists who got accredited by the Russian occupants, ended up in the "Myrotvorets" database and complained about it. However, in a respective article from 2016, his own words work against him. The journalist quotes his critics’ arguments, according to which such coverage serves Russian propaganda. In the very next paragraph, though, he writes about a list of journalists who "applied for press passes to work in territory controlled by the Donetsk People’s Republic, Ukraine’s main enemy in the two-year-old war in the east." To dispel any doubts one may still have, the material also mentions "reporting both sides of the war, including the pro-Russian rebel side." In 2020, “Detector Media” even came up with a dedicated material after Kramer had called the war "separatist."

As time went by, Kramer’s similar approach persisted. In an article published on February 20, 2022, Kramer mentions a man who crossed from the occupied territories into the government-controlled ones – or, as the author writes, "made his way into Ukraine [...] Behind him was the Russian-backed separatist enclave known as the Luhansk People's Republic." It is noteworthy that the "separatists" are referred to as a separate entity that Russia only supports. Actually, “the enclaves broke away in 2014” – all by their own.

Another striking example of this two-sided approach can be found in a 2019 material: "Russian-backed separatists who asserted that the new leaders in Kiev were fascists revolted soon after Russia seized the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine".

Still, Kramer sometimes refers to the fictional "republics" as "so-called," reports on Russia’s de-facto control of them and describes the enclaves as a part of the Kremlin's typical strategy, to which it has previously resorted in Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Moldova.

Getting back to the subject of accreditation in the occupied territories, we did not find any Kramer's materials in which he would promote Russia's arguments or legitimize its puppets. Still, some of his materials look strange. Take, for instance, the one titled "Ukraine rebels celebrate their taking of Debaltseve". Indeed, the article contains small elements of reporting on the celebration, as well as comments of the Ukrainian authorities. However, for some reason, the author ends the article with an address of cutthroats’ leader Zakharchenko, who was still alive at the moment: "Today, our opponents are negotiating with us, as they fear us and respect our strength.”

Another report from the occupied territories published in 2015 contains the following sentence: "Many older people have nowhere else to go, and their pensions have been cut off by a hostile government in Kiev." Reporting on the pseudo-elections in the occupied territories in 2014, Kramer compared them with the ones held in other post-Soviet authoritarian states, for instance, in Turkmenistan, which amounted to another instance of Russia-invented “republics’” legitimization by association.

In the last few years, materials of The New York Times’ journalist about Ukraine have not been limited to the coverage of the war anymore. For instance, in 2021, Andrew decided to write about the domination of comedians in Ukraine’s government. The latter is, of course, true. However, the article still contained some manipulations and generalizations. The most obvious among them came at the end of the material in the form of a quote by Dmytro Razumkov. The former Chariman of the Verkhovna Rada commented that Ukrainians had come to watch a comedy but got a horror movie. Kramer noted that Razumkov had himself been replaced in the parliament with a former comedian Ruslan Stefanchuk. If you did not know that Stefanchuk was a comedian, that's because he last played in KVN (popular Soviet and Russian comedy competition TV show broadcast since 1961) in 2002, after which he pursued a career in academia and became a professor of law.

There was a similar story with an article on the nationalist threat to Ukraine, published in February 2022. This is a striking example of how a journalist can tell a false story without resorting to outright lies, merely presenting a selection of quotes and ignoring the context. According to the material, Ukrainian authorities fear the “Democratic Axe” party (whose office is "decorated with several axes and a crossbow") more than the Russian army. A particularly interesting part of the material is the one where Yuri Hudymenko, the party leader, says that he has a rifle, since he is preparing to fight Russians. Kramer immediately hints at the possibility of weapons being used during the protests. 14 days after the article’s publication, Hudymenko went to war with Russia.

At that time, the Ukrainian army started to stop Russia’s advance in maneuver battles - despite Kramer's article of February 1, 2022, according to which our armed forces are outdated, nothing like NATO, and have "relatively low-tech tactics."

Kramer should be equally embarrassed about Azov, which he called "openly neo-Nazi" in 2015. However, even in April 2022, i.e., already during the defense of Azovstal, the journalist took the liberty to produce some very strange quotes: "Clearing the plant could hold particular symbolic value for President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia, who has justified his invasion with the false claim that Ukraine is run by Nazis, and that he is rooting them out. The plant’s defenders include members of the Azov Battalion, a force that does include far-right soldiers, some of them foreign, including white supremacists and people who have been described as fascists." Makes one wonder who was the author of those descriptions – and who is the one seeking to prove Putin’s words.

By the way, when it comes to the support of Russian narratives, the most scandalous story involving Kramer must be his vaccination with “Sputnik V”. The journalist went as far as to whitewash the drug on the pages of The New York Times. He wrote about Russians allegedly indicating a slightly higher effectiveness percentage than the one achieved by their Western colleagues on purpose. "But from the perspective of a recipient, did that matter?" he concluded, though. He argued that skeptics in the West questioned the vaccine’s early approval, rather than its design, and said that a million people had already been vaccinated, so the negative consequences would have been noticeable. He also mentioned the USSR’s medical achievements and quoted the Russia-coined comparison of “Sputnik V” with the simple and effective Kalashnikov assault rifle. Kramer said that it was easier to get vaccinated in Russia than in the US. He concluded with the narrative that vaccines were beyond politics. It is clear that Russia has widely used this story precisely for politics-related matters.

Since the full-scale war started, Kramer's new materials on Ukraine have been published every few days. Generally, they do not contain any blatant manipulations or obvious nods to Russia. The journalist now compliments Ukraine’s authorities, reports on our victories and explains why our country does not want a ceasefire. He says that the country’s population turned out to be not as pro-Russian as the Kremlin had expected – contrary to what an Andrew Kramer argued on February 23, 2022, by the way.

One cannot conclude from the above materials authored by The New York Times journalist that he is a "Russian agent", as some Ukrainians have immediately suggested. One can conclude, however, that he has been watching our country from Moscow for too long, and it may thus be a problem for Ukraine, if Kramer, as the head of the bureau, passes on such views to his colleagues. The phenomenon of The New York Times, as well as that of journalism in general, is based on reputation. Andrew Kramer has earned his reputation in Russia, but has lost it in Ukraine several times already.

Collage by "Detector Media"